Egypt in England Newsletter

2015

January

The Mystery of Lot 279

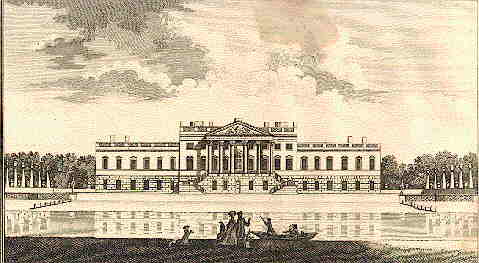

Wanstead House (Wikimedia Commons)

In the summer and autumn of 1822, when the contents of Wanstead House were sold at auction to meet the crippling debts run up by William Pole-

“A ditto [another stone pedestal] with curious Egyptian stone ornament on the top, sculptured in hieroglyphs.”

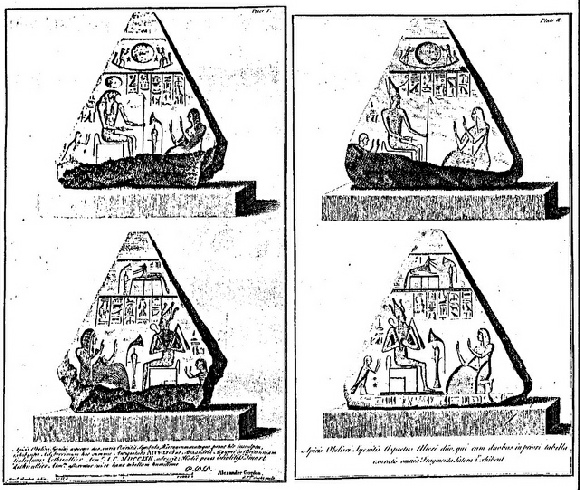

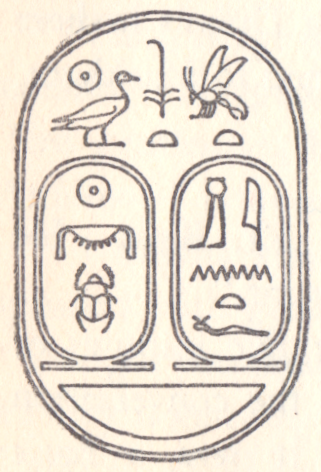

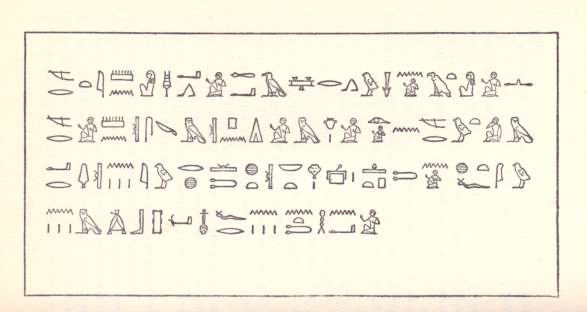

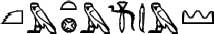

The “ornament” was actually a pyramidion, the pyramid shaped capstone from the tomb monument of Tia, a brother-

Smart was a celebrated antiquarian, and had became a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1724. In 1737 the Secretary to the Society of Antiquaries (and occasional operatic tenor) Alexander Gordon published An Essay toward explaining the Hieroglyphical Figures on the Coffin of the Ancient Mummy belonging to Capt. William Lethieullier. This work also illustrated the pyramidion of Tia, which was by then in the possession of Smart, and means that we have a very good idea what it looked like.

(Courtesy of Ralph Potter)

Smart, the owner of Aldersbrook House in Essex, died in 1760, and although he bequeathed both the pyramidion and the naos to the British Museum, they never reached it. He was friendly with his neighbour at Wanstead House, John, 2nd Earl Tylney, who shared his interest in antiquities, and both pieces may have been loaned or given to Tylney during Smart's lifetime, or been acquired when the manor and lands of Aldersbrook were purchased in 1786 by Sir James Tylney Long from Mary, the daughter of Smart's sister-

However it got there, we know that the pyramidion was in the gardens at Wanstead House in 1792, as it was described by the Danish antiquarian Georg Zoëga in his book on Egyptian obelisks De Origine usu Obeliscorum. The owner of Wanstead House at that time, Sir James Tylney Long, nephew of John Tylney, died in 1794 and was succeeded by his son, also called James, who died aged 11. The estate then passed to his sister Catherine, who became one of the richest, and most eligible, heiresses of her day. In 1812 she married William Pole-

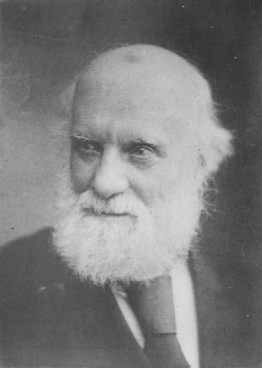

Several catalogues for the sale at Wanstead House have survived, and one is marked with the prices and buyers of many lots, but has nothing for Lot 279 apart from a cryptic note suggesting that it may have been among items held over to another day for lack of time. A second sale was indeed held, of lots "deferred at the late sale, together with various uncleared lots", but there are no known annotated copies of the second catalogue. Then the pyramidion vanishes. In 1882 the clergyman and collector Rev. Greville John Chester wrote to Samuel Birch, then Keeper of Oriental Antiquities at the British Museum, to say that he had seen "a very curious basalt pyramidion" in the Oxford Street shop of the antiquities dealer David Jewell, and describing it in terms which correspond with the engraving in Gordon's work. Chester urged Birch to view the pyramidion "before it is snapped up", but if Birch did he failed to secure it, and if it was the pyramidion of Tia its whereabouts is now unknown. Other than this tantalising clue, there has been no trace of it, from that day to this.

Then, in May 2013, a chance conversation between myself and Ralph Potter of the Friends of Wanstead Park was followed by someone asking him about a mysterious granite stone embedded in the bank of the Heronry Pond, and used as an Ordnance Survey benchmark, raising the tantalising possibility that this might be the long-

Then, in May 2013, a chance conversation between myself and Ralph Potter of the Friends of Wanstead Park was followed by someone asking him about a mysterious granite stone embedded in the bank of the Heronry Pond, and used as an Ordnance Survey benchmark, raising the tantalising possibility that this might be the long-

Meanwhile, however, there was to be yet another twist in the story. In May 2014 another copy of the Wanstead House sale catalogue emerged. This, unusually, had ruled interleaved pages with columns for pounds, shillings and pence, thicker covers, and gilded page edges. It had only one annotation – for Lot 279.

Samuel Birch (Wikimedia Commons)

“Brought from Egypt by Col. Lord Tilney [sic] and presented by Mr Robins to Thomas Bramall and now in garden at Tamworth.”

The auctioneers for the sale were Messrs Robins, father and son, and Robins senior, who had acquired Tamworth Castle in settlement of a debt, restored it for his son-

The Heronry Pond stone (courtesy of Ralph Potter)

Later in January this year, the Heronry Pond stone will at last be excavated. Most likely, what will emerge will be simply a lump of granite. Except that... an expert opinion on the portion currently above ground suggested that it was not, as might be expected, Aberdeen granite, but a granite from Aswan in Egypt. So it might, just possibly, be the long-

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

February

The Mystery of Lot 279 -

What is archaeology about? It seems that in the popular imagination, an archaeologist is Indiana Jones or Lara Croft, unearthing hidden treasures and ancient artefacts.

(Image courtesy of Michael Neel.)

It's all about danger, derring-

On January 22nd, members of the West Essex Archaeology Group excavated the mysterious stone in Wanstead Park. (See last issue.) The day was bright and dry, if cold, and we had not one, but two Egyptologists present, in the shape of Chris Naunton, Director of the Egypt Exploration Society, and Geoffrey Martin, Emeritus Edwards Professor of Egyptology at University College London. It would be wonderful to describe how, as the topsoil was removed, and the stone delicately scraped clear with trowel and brush, the outlines of carved reliefs and incised hieroglyphs began to emerge. Unfortunately, they didn't. The Heronry Pond stone was definitely not the lost Pyramidion of Tia. Not even in a battered and mutilated state.

So was the whole exercise a waste of time? Only if you subscribe to the treasure hunting view of archaeology. Because ultimately it wasn't about an artefact, it was about information. Even a once in a lifetime discovery, like the tomb of Tutankhamun, is about more than Carter's "gold -

In this case it was about what we didn't find, and the questions we asked as a result. At the end of the Sherlock Holmes story 'Silver Blaze', the following exchange takes place between Holmes and Inspector Gregory:

"Inspector Gregory: ‘Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?’

Sherlock Holmes: ‘To the curious incident of the dog in the night time.’

Inspector Gregory: ‘The dog did nothing in the night time.’

‘That was the curious incident,’ remarked Sherlock Holmes."

(© Chris Elliott 2015)

ABE Commemorated

Elsewhere in London, March 19th should see the long-

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

March

Honouring Amelia

Seven years is a long time, but on Thursday 19th March a process that had started in 2008 finally came to its conclusion at 19 Wharton Street in Islington, when an English Heritage Blue Plaque honouring Amelia Edwards was unveiled. The scheme has been run in various incarnations since 1866 by the Royal Society of Arts, the London County Council, the Greater London Council, and since 1986 by English Heritage. In that time, nearly 900 plaques (all known as Blue Plaques, even though some of them aren't blue) have been set into buildings all across London, but only two of them commemorated Egyptologists. The first, erected by the London County Council in 1954 at 5 Cannon Place NW3, was for Abu Bagousheh, the Father of Pots, better known as the pioneer of modern Egyptology Sir Flinders Petrie. It was not until 1999 that the second, at 19 Collingham Gardens SW5, marked a London residence of Howard Carter, excavator of the tomb of Tutankhamun. I may be biased, but two Egyptologists out of a total of nearly 900 plaques in 142 years didn't seem excessive to me, and so I proposed Amelia Edwards for one.

Amelia Ann Blandford Edwards, known to friends and family as Amy, and to colleagues as ABE, was a remarkable woman. She was a talented singer and musician, and could have practised either or both professionally, but after breaking off an early engagement because "although he loved me very much I could not really love him"1 she remained unmarried, and was instead to pursue a very successful career as a professional writer. Literary tastes have changed, and her novels and short stories are little read now, and then probably mostly by academics, but in her day she sold well, and some of her ghost stories in particular are still anthologised. She also wrote and edited non-

Amelia Ann Blandford Edwards, known to friends and family as Amy, and to colleagues as ABE, was a remarkable woman. She was a talented singer and musician, and could have practised either or both professionally, but after breaking off an early engagement because "although he loved me very much I could not really love him"1 she remained unmarried, and was instead to pursue a very successful career as a professional writer. Literary tastes have changed, and her novels and short stories are little read now, and then probably mostly by academics, but in her day she sold well, and some of her ghost stories in particular are still anthologised. She also wrote and edited non-

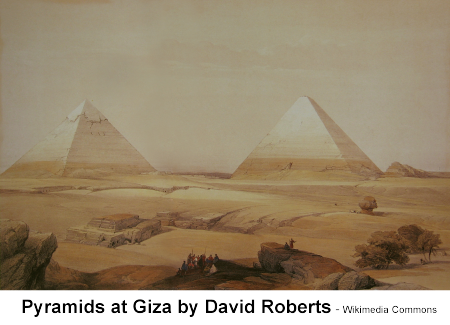

Famously, it was a visit to Egypt when she was forty-

"Standing there close against the base of it [the Great Pyramid]; touching it; measuring her own height against one of its lowest blocks; looking up all the stages of that vast, receding, rugged wall, which leads upward like an Alpine buttress and seems almost to touch the sky, the Writer suddenly became aware that these remote dates had never presented themselves to her mind until this moment as anything but abstract numerals. Now, for the first time, they resolved themselves into something concrete, definite, real. They were no longer figures, but years with their changes of season, their high and low Niles, their seed-

As well as seeing the surviving monuments of Ancient Egypt, and carrying out a modest excavation with her companions at Abu Simbel, she also witnessed the damage and destruction being caused to the antiquities by the drive to transform Egypt into a modern industrial nation on the European model. From this point on, the preservation, scientific excavation and accurate recording of the remains of Ancient Egypt became her mission. With the support of R S Poole of the British Museum, and Sir Erasmus Wilson, who was also instrumental in bringing Cleopatra's Needle to London, she founded the Egypt Exploration Fund, which eventually became the Egypt Exploration Society. Sacrificing her own writing career, she became Secretary of the Fund, and a tireless promoter of its aims through articles in popular magazines and scholarly journals, later touring the USA to lecture there. The Fund's excavations were instrumental in launching the careers of both Flinders Petrie and Howard Carter, and today the society that she helped found is doing the same for early career Egyptologists through its Centenary Fund. After her death, her will left her library and Egyptian antiquities collection to University College London, and funds to establish the first chair in Egyptian Archaeology and Philology in England there, the Edwards Professorship.

At the Blue Plaque unveiling ceremony, which was introduced by Professor Sir Christopher Frayling, a member of the Blue Plaque Committee, and also the author of 'The Face of Tutankhamun', the other speakers were the Emeritus Edwards Professor at UCL, Geoffrey Thorndike Martin, Professor Joanne Fletcher, Director of the Egypt Exploration Society Dr Chris Naunton, and papyrologist and Society Trustee Dr Margaret Mountford, who pulled the cord to unveil the plaque.

(Left to right, back row, Dr Chris Naunton, Prof. Geoffrey Martin and Prof. Sir Christopher Frayling, front Chris Elliott, Dr Margaret Mountford, Prof. Joanne Fletcher. Inset, Prof. Fletcher in ‘Team Amelia’ t-

Brenda Moon's biography of Amelia Edwards, 'More Usefully Employed', is available from the Egypt Exploration Society at the very reasonable price of £5. Click on the cover image to find out more, and if you aren't already a member of the Egypt Exploration Society, consider becoming one, and helping to preserve the legacy of a woman who achieved so much in a very practical way.

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

1. Quoted in 'More Usefully Employed', Brenda Moon, p. 14

2. 'A Thousand Miles Up The Nile', Amelia Edwards, p. 2

3. 'A Thousand Miles Up The Nile', Amelia Edwards, p.15

April

From An Antique Vase...

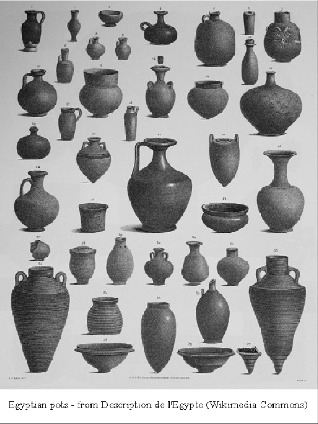

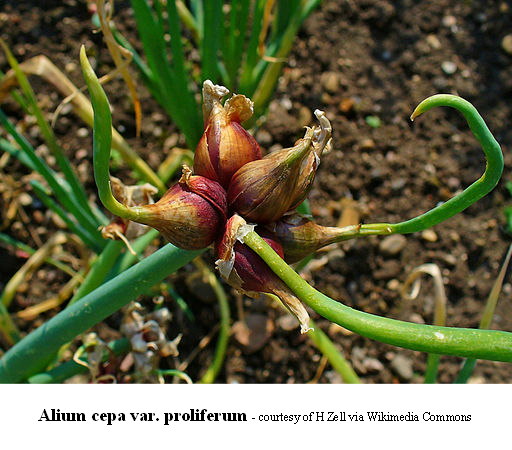

Myths about Ancient Egypt are extraordinarily persistent, perhaps, as one commentator observed, because they are "interesting, coherent, and easily expressed". They not only seem to endure for ever, but they are also remarkably pervasive, linking all sorts of different groups within a culture. What Egyptian connection, for example, could link the scientist Michael Faraday with Mrs Beeton (of Book of Household Management fame), a Nobel Prize- The story goes back to the first half of the nineteenth century, and two pioneers of the newly emerging discipline of Egyptology. One was Sir J G Wilkinson, who has a good claim to be the founder of British Egyptology, and the other was Thomas Pettigrew, author of the first comprehensive modern study of mummification, and probably the foremost unroller of Egyptian mummies. Wilkinson had presented to the British Museum "an antique vase, hermetically closed, which he had found in a mummy pit in Egypt, and the age of which was computed at about three thousand years". Pettigrew attempted to open it, but this resulted in the vase breaking into pieces. Inside was "a mass of vegetable dust", but also a few grains of wheat and a number of rock hard shrivelled peas. Pettigrew distributed the grains "among a few of his learned friends", who tried planting them to see if they would grow. Their efforts were in vain, as they simply rotted away. But that was not the end of the story.

The story goes back to the first half of the nineteenth century, and two pioneers of the newly emerging discipline of Egyptology. One was Sir J G Wilkinson, who has a good claim to be the founder of British Egyptology, and the other was Thomas Pettigrew, author of the first comprehensive modern study of mummification, and probably the foremost unroller of Egyptian mummies. Wilkinson had presented to the British Museum "an antique vase, hermetically closed, which he had found in a mummy pit in Egypt, and the age of which was computed at about three thousand years". Pettigrew attempted to open it, but this resulted in the vase breaking into pieces. Inside was "a mass of vegetable dust", but also a few grains of wheat and a number of rock hard shrivelled peas. Pettigrew distributed the grains "among a few of his learned friends", who tried planting them to see if they would grow. Their efforts were in vain, as they simply rotted away. But that was not the end of the story.

"It happened, however, that Mr Pettigrew kept three grains for curiosity sake, which, after the lapse of several years, he presented, as one of the greatest antiquities of the vegetable world, to Mr W Grimstone, the well-

Grimstone's Egyptian Pea

In June 1844 Grimstone planted the 'grains', which were actually peas, in "an artificial mould resembling, as nearly as possible, the alluvial soil of Egypt". After the application of "incredible care", after thirty days one of the peas sprouted. However, the resulting plant was "shrivelled, very weakly, almost without colour, and promised anything but a long life". All was not lost, though, as "Art came to the aid of nature", and after intensive care the plant was sturdy enough to be transplanted from the greenhouse into an outside bed. Here it matured, flowered, and produced its own peas, which when planted in turn "succeeded completely".

The quotes above are from the February 1849 issue of The Gardener, Florist, and Agriculturist, and the article goes on to reveal that Mr Grimstone, flushed with success, "addressed himself to Dr Plate, the secretary of the Syro-

The story of the Egyptian vase certainly seems to be based in fact, as Pettigrew referred to it in at least one of the lectures with which he accompanied his mummy unrollings, and a letter survives from J G Wilkinson to Pettigrew in which Wilkinson, intrigued by newspaper reports that some of the peas he had given Pettigrew had germinated, asks for more information, and at the same time provides confirmation that while unpacking items at the British Museum in 1833 or 1834 he had indeed given some seeds to Pettigrew.

It is not especially clear why several years later Pettigrew should have presented the three surviving peas to Mr Grimstone, if indeed he did, or what their connection was, but what is clear is that Grimstone was not only anxious that the public should be aware of his success, but that they should be able to repeat it themselves. We know from a newspaper advertisement that the owner of the Highgate Herbary sold his 'Egyptian Pea' in signed and sealed bags, including reproductions of two letters by J G Wilkinson (implying, but not stating, that they were on the topic of mummy peas) at half a crown a bag, boasting not only of the superior quality of the resulting crop, but that it would produce enough to supply a small family. This price, two shillings and sixpence, corresponds to about £8 in modern currency, and those of you who garden can compare this with what you usually pay for seeds. A cynic might also observe that in terms of a potential market, while few Victorian families grew wheat in their gardens, many grew peas. Grimstone himself was a purveyor of patent medicines, and seems to have been something of a chancer. A year after Plate's lecture he was declared bankrupt after being prosecuted for evasion of excise duty, although he did not go out of business as a result. Viewed in this light, it is not surprising that Plate's lecture reads like a recycled press release, and part of some opportunistic PR on Grimstone's part.

Vegetables From The Tomb

But what of Mummy Wheat? Surely this is more than dodgy marketing and PR? The earliest reference to Mummy Vegetables I am currently aware of is in The Times in 1832, which actually referred to a 'bulbous root', probably an onion, found in the hand of an Egyptian mummy, that had been successfully planted and grown, but the Gardener article notes that:

“At that time [presumably 1833-

Certainly, by the 1840s the belief that wheat thousands of years old from Egyptian tombs had been grown successfully was widespread. A letter of January 1842 from the Orientalist Edward Lane to the traveller and collector Robert Hay reveals that Lane gave Wilkinson the corn said to have been found by Wilkinson in a mummy case “which has been so much puffed” (i.e. in the press), and mentions Hay's intention to try and germinate more of the same grain given by Lane to Hay. (BL Add Ms 38510 F.179) In June 1843 the celebrated scientist Michael Faraday, who examined material from Pettigrew's mummy unrollings, read to a meeting of the Royal Institution extracts from a note he had received from the writer and poet Martin Tupper on Tupper's allegedly successful planting of Mummy Wheat. By 1861 Mrs Isabella Beeton could note very matter-

Certainly, by the 1840s the belief that wheat thousands of years old from Egyptian tombs had been grown successfully was widespread. A letter of January 1842 from the Orientalist Edward Lane to the traveller and collector Robert Hay reveals that Lane gave Wilkinson the corn said to have been found by Wilkinson in a mummy case “which has been so much puffed” (i.e. in the press), and mentions Hay's intention to try and germinate more of the same grain given by Lane to Hay. (BL Add Ms 38510 F.179) In June 1843 the celebrated scientist Michael Faraday, who examined material from Pettigrew's mummy unrollings, read to a meeting of the Royal Institution extracts from a note he had received from the writer and poet Martin Tupper on Tupper's allegedly successful planting of Mummy Wheat. By 1861 Mrs Isabella Beeton could note very matter-

“The Egyptian, or Mummy Wheat, is not grown to any great extent, owing to its inferior quality; but it is notable for its large produce, and is often cultivated on allotment grounds and on small farms, where quantity rather than quality is desired.”

Book of Household Management Chap 35.

Baron Nettelbladt's Electric Apparatus and the Bearded Russian

Despite the widespread belief that seeds, grains and bulbs from Ancient Egyptian tombs could be successfully grown thousands of years later, as early as January 1843 the Gentleman's Magazine confessed that it had been “somewhat sceptical about the sprouting of the corn of Misraim's land, preserved through countless ages”, while conceding that “Mr Pettigrew's experience goes far to remove our doubts.” By 1895, however, William Carruthers, head of the Botanical Department at the Natural History Museum in London, could acidly observe that:

“It would be no greater wonder to see the hardened and eviscerated mummy, under favourable treatment, rise up and walk, than to see the grains found in its cerements germinate.”

(Nature Notes, 1895)

Many, however, would have pointed out what they felt to be unarguable proof to the contrary – that they had planted and grown seed taken from tombs and the cases and wrappings of mummies. The explanation for this, put forward in 1922 in the Guide to the Egyptian Rooms at the British Museum, was that Ancient Egyptian tombs were used by modern Egyptians to store wheat, which would germinate if not too old. There are also examples of mummies in transit being stored in stable buildings, where they could also easily be contaminated in this way.

In September 1934 Wallis Budge, previously Keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities at the British Museum, did his best to dispel what he described as “hundred year old nonsense about mummy wheat'” by offering to “responsible” institutions for germination experiments samples of wheat taken from a 19th Dynasty tomb which he had excavated in 1906. Those taking him up on the offer included the National Institute of Agricultural Botany in Cambridge, and Farmer's Weekly. They also included one Baron Nettelbladt, who noted in a letter to Budge that “I have a large ultra-

Still, however, the myth of mummy wheat refused to die, as a letter to Budge from a Canadian correspondent in Provost, Alberta shows

“The idea prevalent among many of the farmers of this province is that mummy wheat' produces crops of astonishingly high yield. Unscrupulous salesmen prey upon these misguided individuals accordingly, very often peddling to them, as 'mummy wheat' very inferior varieties of wheat similar to the bearded Russian variety. Naturally, these salesmen demand, and secure, very exorbitant prices for their wheat.”

Helping to perpetuate the vegetable mummy myth, the name of Mummy Pea seems to have been given to a variety of crown flowered pea, and unusual and exotic looking vegetables (including beetroot) could be described as 'Egyptian' in the 19th century. (Personal communication from Rebsie Fairholm, who grows 'rare breed' vegetables.)

Little Women, a Black Centaur, and Internet immortality

Writers and poets have helped to keep the myth alive as well. Lost in a Pyramid, an 1869 story by the author of Little Women, Louisa May Alcott, referred to wheat “taken from a mummy's coffin” that had sprouted and grown. In a poem to a friend, the Poet Laureate Alfred Lord Tennyson claimed that

Writers and poets have helped to keep the myth alive as well. Lost in a Pyramid, an 1869 story by the author of Little Women, Louisa May Alcott, referred to wheat “taken from a mummy's coffin” that had sprouted and grown. In a poem to a friend, the Poet Laureate Alfred Lord Tennyson claimed that

“...here the torpid mummy wheat

Of Egypt bore a grain as sweet

As that which gilds the glebe of England,

Sunned with a summer of milder heat.”

Later, William Butler Yeats, the Nobel Laureate, referred to mummy wheat in two poems, Conjunctions and On a picture of a black centaur by Edmund Dulac.

These literary uses suggest that a large part of the appeal of mummy wheat, peas, and even onions, stems from the association of Ancient Egypt with mystical longevity, and the power to preserve suspended life over millennia. In modern times, the ability of the Internet to assist the propagation of urban myths as well as scholarship probably means that despite all attempts to break the curse, nothing will stop the mummy vegetables rising from the tomb again...

For more on this topic, see the following

Grimstone and the Mummy Pea – Quack Doctor web site

The Seeds of Doom – Jasmine Day

Mummy Wheat -

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

May

Egypt, Indirectly

What do you bring back when you travel abroad? Memories, certainly. What's the point of going otherwise? Most of us return with photos, and almost all of us bring back some other sort of souvenir. A recent trip to Rome made me think about these things, and how past visitors to the city have been part of the process by which Ancient Egypt has continued to influence us.

It is a process which has been going on for a long time. Rome's associations with the Apostle Peter, the early church and Christian martyrs, as well as its role as the seat of the papacy, have long made it one of the great sites of Christian pilgrimage, including pilgrims from the British Isles. Those with sufficient money or dedication could make the long and dangerous pilgrimage to the Holy Land and Jerusalem itself, often by way of Alexandria and sites in Egypt associated with the Flight of the Holy Family and various saints, but for others who could only go as far as Rome there were still reminders of Egypt and its associations with Christianity. Ordinary mortals bring back souvenirs. Caesars brought back imperial trophies, and foremost among these were obelisks from Egypt. Over the centuries those in Rome were toppled by man and the elements, but at least two remained upright for centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire. One of them was the obelisk brought back by Augustus in 10 BC, and set up in the Campus Martius (Field of Mars) as part of a giant solar meridian, marking the length of the days throughout the year. We know that it remained standing until at least the 8th century AD, as it was referred to then in the Einsiedeln Itinerary, a work which acted as a sort of guide book for pilgrims to Rome with a list of sites and directions. As it was one of the tallest obelisks in the city, it would have been a prominent landmark. Some time after that it fell, perhaps in an earthquake in 849 AD, or during the sack of Rome in 1084. Rediscovered in five pieces in 1512, an attempt was made to re-

Ordinary mortals bring back souvenirs. Caesars brought back imperial trophies, and foremost among these were obelisks from Egypt. Over the centuries those in Rome were toppled by man and the elements, but at least two remained upright for centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire. One of them was the obelisk brought back by Augustus in 10 BC, and set up in the Campus Martius (Field of Mars) as part of a giant solar meridian, marking the length of the days throughout the year. We know that it remained standing until at least the 8th century AD, as it was referred to then in the Einsiedeln Itinerary, a work which acted as a sort of guide book for pilgrims to Rome with a list of sites and directions. As it was one of the tallest obelisks in the city, it would have been a prominent landmark. Some time after that it fell, perhaps in an earthquake in 849 AD, or during the sack of Rome in 1084. Rediscovered in five pieces in 1512, an attempt was made to re-

Imperious Caesar…

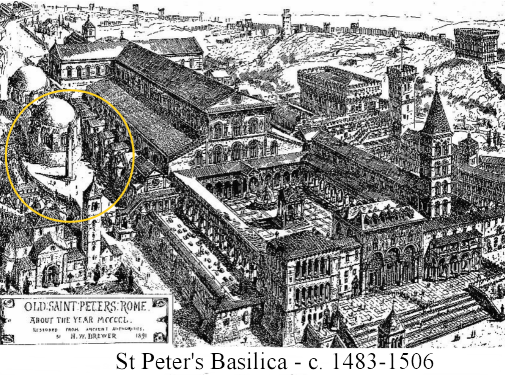

The other obelisk to remain standing in Rome was its second tallest, now in Piazza San Pietro. When the Castilian traveller Pero Tafur visited in the 15th century, it was still in its original position on the site of the Vatican Circus, about 260 metres from where it now stands, to the left of the original basilica of St Peter. (See illustration.)

The obelisk, because of its position, was believed to mark the site of the martyrdom of St Peter, as well as other Christians killed in the Circus during Roman times. Its connection to the Roman emperors was preserved in the belief that the bronze globe on its peak held the ashes of Julius Caesar. Tafur referred to it as “Caesar's Needle”, and described it as a “three-

By the time of the Enlightenment, and the rise of the Grand Tour, souvenirs of a visit to Rome could be much more substantial. Wealthy dilettanti (or their agents) amassed collections of Classical, and sometimes Ancient Egyptian antiquities. Perhaps the ultimate obelisk souvenir, however, would have been that of Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, who travelled in Italy in 1613-

By the time of the Enlightenment, and the rise of the Grand Tour, souvenirs of a visit to Rome could be much more substantial. Wealthy dilettanti (or their agents) amassed collections of Classical, and sometimes Ancient Egyptian antiquities. Perhaps the ultimate obelisk souvenir, however, would have been that of Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, who travelled in Italy in 1613-

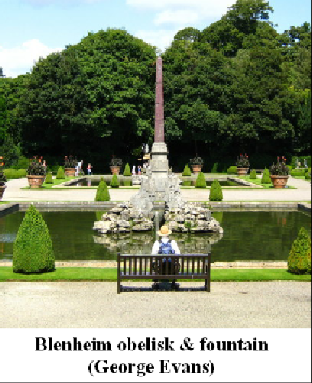

In 1710, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, acquired a scaled down replica of the fountain and obelisk, begun by Bernini and completed after his death by his workshop, which now stands on the north terrace at Blenheim. You may object that this was only a replica, but so are many souvenirs. If you want authenticity, however, look no further than Dr John Bargrave, travelling tutor to the Grand Tourist John Raymond, who visited Italy in 1646-

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

1 Pearce, S. 'Belzoni's Collection and the Egyptian Taste'. In C. Sicca and A. Yarrington eds. The Lustrous Trade: Material Culture and the History of Sculpture in England and Italy, c. 1760-

2 Chaney, Edward 'Roma Britannica and the cultural memory of Egypt: Lord Arundel and the obelisk of Domitian' in Roma Britannica: art patronage and cultural exchange in eighteenth-

In a strange way, however, it did reach England. In 1710, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, acquired a scaled down replica of the fountain and obelisk, begun by Bernini and completed after his death by his workshop, which now stands on the north terrace at Blenheim. You may object that this was only a replica, but so are many souvenirs. If you want authenticity, however, look no further than Dr John Bargrave, travelling tutor to the Grand Tourist John Raymond, who visited Italy in 1646-

In a strange way, however, it did reach England. In 1710, John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, acquired a scaled down replica of the fountain and obelisk, begun by Bernini and completed after his death by his workshop, which now stands on the north terrace at Blenheim. You may object that this was only a replica, but so are many souvenirs. If you want authenticity, however, look no further than Dr John Bargrave, travelling tutor to the Grand Tourist John Raymond, who visited Italy in 1646-

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

1 Pearce, S. 'Belzoni's Collection and the Egyptian Taste'. In C. Sicca and A. Yarrington eds. The Lustrous Trade: Material Culture and the History of Sculpture in England and Italy, c. 1760-

2 Chaney, Edward 'Roma Britannica and the cultural memory of Egypt: Lord Arundel and the obelisk of Domitian' in Roma Britannica: art patronage and cultural exchange in eighteenth-

June

The corners of a foreign field, that are forever Giza

Come out of Holborn tube station onto Kingsway, and turn left. Walk south for about 150 yards and turn left again into Remnant Street, then follow it until it ends at Lincoln's Inn Fields. The largest of London's garden squares, it is both attractive and impressive, but your immediate reaction would, almost certainly, not be to remark on how similar it is in size to the base of the Great Pyramid at Giza. Yet there is a stubbornly persistent tradition that this is not only the case, but that it was specifically intended to be so.

In 1847, a panorama of Cairo was exhibited at the Royal Panorama in Leicester Square. It was painted by the proprietor Robert Burford and his assistant H C Selous from drawings by the artist David Roberts, famous for his series of lithographs of Egypt and Nubia. The pamphlet for this panorama, as well as offering Roberts an opportunity to publicise his forthcoming work, commented that:

€œ”To use a familiar illustration, it [the Great Pyramid] is about the height of St Paul's, and covers a space equal to the area of Lincoln's-

(British Library, Pamphlets collection.)

You might think that this was just a helpful analogy, but nearly twenty years later in 1866 Joseph Bonomi, the artist and pioneer Egyptologist who had become Curator of Sir John Soane's Museum, went so far as to measure the area of the Fields and compare it to the area of the base of the Great Pyramid. London Metropolitan Archives still has his pen and ink drawing on tracing paper which shows the rectangle of the square, with the names of the roads coming into it, and superimposed on it a shaded square outlined in red ink showing the size of the pyramid's base. Neatly written below the diagram is a note "Comparative areas of Gt. Pyramid of Gizeh and the Square of Lincoln's Inn Fields, the red lines indicate the pyramid". Below this is a sum comparing the two areas, and showing the area of the pyramid's base to be greater, and the note "Measured by Joseph Bonomi. Soane Museum. 1866". Bonomi knew Egypt and its antiquities probably as well as anyone of his time, and was also well acquainted with panoramas. While in Egypt with the great Lepsius expedition in 1842 he painted a watercolour panorama of the view from the top of the Great Pyramid, and drawings by him were the basis for Warren and Fahey's moving panorama of the Nile which exhibited at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly from 1849. Because of its theme, it is quite likely that he visited the Leicester Square panorama, and purchased the pamphlet accompanying it. So was he simply curious to see if the comparison was true?

Transported bodily to London

Had this been the case, it is unlikely that it would be mentioned by others. 1877 saw the publication of both Amelia Edward's A Thousand Miles Up The Nile and Erasmus Wilson's Cleopatra's Needle and Egyptian Obelisks, both of which mentioned it. Edwards said that if the Great Pyramid were "transported bodily to London, it would a little more than cover the whole area of Lincoln's Inn Fields" (A Thousand Miles Up The Nile pp. 15-

Had this been the case, it is unlikely that it would be mentioned by others. 1877 saw the publication of both Amelia Edward's A Thousand Miles Up The Nile and Erasmus Wilson's Cleopatra's Needle and Egyptian Obelisks, both of which mentioned it. Edwards said that if the Great Pyramid were "transported bodily to London, it would a little more than cover the whole area of Lincoln's Inn Fields" (A Thousand Miles Up The Nile pp. 15-

€œIn order clearly to realise its [the Great Pyramid's] dimensions, we must imagine the great square of Lincoln's Inn Fields, where the area is exactly that of the Great Pyramid and covering this space we must imagine a mass of stone building the height of the Cathedral at Strassburg.€

(A Handbook of Egyptian Religion P. 117, Griffith's 1907 English translation.)

The tradition was still alive in 1928, when the Architectural Review (Vol. 63, p. 68) commented that most London 'squares' were far from being square. It went on to observe that Lincoln's Inn Fields were more nearly rectangular than most, and:

"still more so when it is further remembered that the commission which laid it out in 1618, and of which Inigo Jones and Francis Bacon were members, would probably have made it a perfect quadrate, had they not for some recondite reason determined that its lines should exactly correspond with the base of the Great Pyramid".

The commission referred to had been set up following a petition to James I in 1617 by the Society of Lincoln's Inn and the four adjoining parishes that the two common fields which came to be Lincoln's Inn Fields should not be built on, but turned into a public space. The monarch was supportive, and in words that have an ironic ring in today's London the Privy Council encouraged the various authorities to proceed with the project:

"as a meanes to frustrate the covetous and greedy endeavours of such persons as daylie seek to fill upp that small remainder of Ayre in those partes with unnecessary and unprofitable Buildinges".

(Survey of London Vol 3 Part 1)

Inigo Jones is believed to have produced plans for laying out the fields into walks, and these seem to have survived in the collection of Lord Pembroke at Wilton House until some time in the 19th century, but to have since been lost. But there is no reason to believe there was anything about them that explicitly suggested a link with the Great Pyramid. So where did the idea come from?

The like dimensions

The answer may lie not in London, but in Wiltshire, and not with the Great Pyramid, but with Stonehenge. In 1620, Inigo Jones was commissioned by James I to study the ruins of Stonehenge, and eventually concluded that it had been built by the Romans. Subsequent antiquarians disputed this view, including John Evelyn who believed it had been built by the Ancient Britons and their Druid priests, and in 1740 the Rev. William Stukeley (a founder member of the first Egyptian Society in London) reasserted this view in his book Stonehenge, a Temple Restor'd to the British Druids. Stukeley, who believed that there were connections between the Druids and the Ancient Egyptians, wrote that:

"the side of the greater pyramid at base, is 693 English feet; which amounts exactly to 400 Egyptian cubits...I have taken notice that Inigo Jones observ'd the like dimensions, in laying out the plot of Lincoln's-

(Quoted by Vaughan Hart, Art and Magic in the Court of the Stuarts p. 134)

Was Stukeley right to claim that Jones had made this link? We know that Jones travelled to Italy in 1613 in the entourage of the 14th Earl of Arundel, who attempted to buy and bring to England the Obelisk of Domitian now in the Piazza Navona in Rome (see the May issue of this newsletter). We know also that Jones had in his library a number of works on the antiquities of Rome. (See Chaney, reference at end.) These included Andrea Fulvio's Antichità della città di Roma, the works on architecture of Sebastiano Serlio, and Le Cose maravigliose dell'alma città di Roma, a guide to the city for foreign tourists which mentioned both its obelisks and the Pyramid of Cestius. In particular, Book 3 of Serlio's work dealt with Ancient Egyptian architecture, and included material from the Venetian Marco Grimani, who visited Egypt 1535-

Was Stukeley right to claim that Jones had made this link? We know that Jones travelled to Italy in 1613 in the entourage of the 14th Earl of Arundel, who attempted to buy and bring to England the Obelisk of Domitian now in the Piazza Navona in Rome (see the May issue of this newsletter). We know also that Jones had in his library a number of works on the antiquities of Rome. (See Chaney, reference at end.) These included Andrea Fulvio's Antichità della città di Roma, the works on architecture of Sebastiano Serlio, and Le Cose maravigliose dell'alma città di Roma, a guide to the city for foreign tourists which mentioned both its obelisks and the Pyramid of Cestius. In particular, Book 3 of Serlio's work dealt with Ancient Egyptian architecture, and included material from the Venetian Marco Grimani, who visited Egypt 1535-

The job of the commission in which Inigo Jones played a part seems essentially to have been to survey the then current state of the fields, recording what we would now think of as structures or buildings erected without planning permission, and producing proposals for laying them out as a public space, not the overall planning and design of the area and buildings around the fields. In practical terms, it had little if any influence on the subsequent development of the area. In the absence of any firm evidence that Jones intended a link between the dimensions of Lincoln's Inn Fields and the pyramid, it may be more likely that it was Stukeley, considered eccentric even in his own time, who made the link, and believed the Fields to have been created as some sort of symbolic footprint or presence of the Great Pyramid and Ancient Egypt, who thought that behind the sober English feet and inches of London's largest square were corners of a foreign field 400 cubits on a side that would be forever Giza.

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

Chaney, Edward 'Roma Britannica and the cultural memory of Egypt: Lord Arundel and the obelisk of Domitian' in Roma Britannica: art patronage and cultural exchange in eighteenth-

July

Return of the Vegetables from the Tomb…

The April issue of this newsletter, which dealt with the hardy perennials that are Mummy Wheat and Mummy Peas, also briefly referred to an article in The Times of April 25th 1832. Not only is this the earliest reference to mummy vegetables that I have so far come across, but it also introduces another category, that of mummy onions.

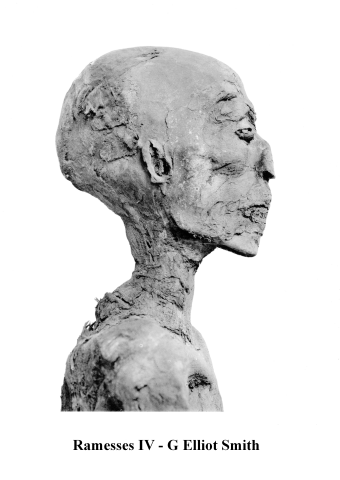

The Times piece can be linked to lectures delivered by George Augustus Rees MD in December 1831 and February 1832 at the Mechanics' Institute (probably the London Mechanics' Institute, which became Birkbeck College), which were later published as Lectures (delivered at the Mechanics Institution, 19th Dec., 1831, and 13th Feb., 1832,) on carbon, oxygen and vitality, the three great agents in the physical character of Man. With remarks on Asiatic Cholera. (The second cholera pandemic had started in 1831, and reached London in 1832.) In the course of these lectures, Rees mentioned a “bulbous root”, almost certainly one of the onion family, found in the hand of an Egyptian mummy, which had allegedly been successfully planted and grown. Onions were not only an important food in Ancient Egypt, and frequently depicted in offering scenes, but their presence in mummy wrappings indicates that they also had religious significance. This may have been because, like the wheat found in Osiris figures in tombs, they had the apparently miraculous ability to regenerate when buried, and also because of their antibacterial properties, which would have been associated with health and vitality. (Part of me can't help thinking of another link. To paraphrase a line from the film Shrek, “Mummies are like onions. They have layers.”) They have been found in the chest and pelvic regions of mummies, against the ears, along legs and on the soles of feet, and, most famously in the case of the mummy of Ramesses IV, in the eye sockets.

The Times piece can be linked to lectures delivered by George Augustus Rees MD in December 1831 and February 1832 at the Mechanics' Institute (probably the London Mechanics' Institute, which became Birkbeck College), which were later published as Lectures (delivered at the Mechanics Institution, 19th Dec., 1831, and 13th Feb., 1832,) on carbon, oxygen and vitality, the three great agents in the physical character of Man. With remarks on Asiatic Cholera. (The second cholera pandemic had started in 1831, and reached London in 1832.) In the course of these lectures, Rees mentioned a “bulbous root”, almost certainly one of the onion family, found in the hand of an Egyptian mummy, which had allegedly been successfully planted and grown. Onions were not only an important food in Ancient Egypt, and frequently depicted in offering scenes, but their presence in mummy wrappings indicates that they also had religious significance. This may have been because, like the wheat found in Osiris figures in tombs, they had the apparently miraculous ability to regenerate when buried, and also because of their antibacterial properties, which would have been associated with health and vitality. (Part of me can't help thinking of another link. To paraphrase a line from the film Shrek, “Mummies are like onions. They have layers.”) They have been found in the chest and pelvic regions of mummies, against the ears, along legs and on the soles of feet, and, most famously in the case of the mummy of Ramesses IV, in the eye sockets.

The “bulbous root” also provides a link to Martin Farquhar Tupper. As you may remember, in June 1843 Michael Faraday read a meeting of the Royal Institution extracts from a note he had received from Tupper describing his allegedly successful planting of mummy wheat. Writing from Brighton, Tupper enthused about his:

“" resuscitated Mummy-

(The Year-

Years later, in the introduction to a biography of Tupper (Martin Tupper, his Rise and Fall by Derek Hudson) his grandson, the Rev. Martin E Tupper, was to recall a jar of mummy wheat in the family house near Crystal Palace in London.

So who was Martin F Tupper? Congratulations if you recognised him as the best selling Victorian author of Proverbial Philosophy, which went through at least forty editions in Britain, and sold nearly one million copies in the United States. Virtually forgotten nowadays, Tupper was a prolific and highly successful author in his time, but the homespun moralising of Proverbial Philosophy, which perfectly suited middle class Victorian tastes, now seems trite and contrived. Among the more than four hundred pages of the book, the section Of Authorship has this to say about the Land of the Pharaohs:

“Egypt, wondrous shores, ye are buried in the sand-

of forgetfulness!

Alas, -

young,

And none durst wrestle with that angel, iron-

bride-

So he flew by strong upon the wind, nor dropped one

failing feather

Wherewith some hoary scribe might register your honour and renown”

His cultivation of Mummy Wheat suggests that Tupper was interested in Ancient Egypt, and indeed he seems to have had a small collection of Ancient Egyptian antiquities, and to have been fairly well read on the subject of Ancient Egypt. Another of his works was A Modern Pyramid: to commemorate a Septuagint of Worthies, sonnets and essays on seventy famous men and women, including the biblical figures of Joseph and Moses. (The original Septuagint were the seventy, or in some sources seventy-

“the hieroglyphical researches of M. Champollion have established that the use of papyrus was long anterior to the age of Moses: there being now extant at Turin an Egyptian writing on papyrus, expounded to be an act of Thutmosis III, and accounted two hundred years older than the time of the Pharaoh, in whose reign Moses flourished.”

Returning to the topic of Mummy Onions, Tupper must have known of George Rees's lectures, as one of his poems is the rather cumbrously titled On A Bulbous Root (Which Blossomed, After Having Lain For Ages In The Hand Of An Egyptian Mummy). Those of you with the interest and stamina to read all one hundred and thirty-

“What emblem liker, or more eloquent

Of immortality,-

Scarab, or circled snake, or wide-

The azure-

The pyramid four-

Or all whatever else were symbols apt

In Egypt's alphabet,-

So full of living promise?”

However, as I noted in the April newsletter, modern research has shown that the DNA of ancient wheat is so degraded that germination would be impossible, and the same would be true for peas and onions. But while science may seem to have demolished the romantic myth of mummy vegetables, as we know it is remarkably persistent, and before the swift and remorseless passage of the iron-

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

August 2015

Encomia for the Embalmed, or Ditties to the Dessicated

After a positive banquet of mummy vegetables over the last two newsletters, with Mummy Wheat, Peas and Onions, I almost hesitated to return to the subject of mummies again. This time, however, it is the verse that they have inspired, since Martin Farquhar Tupper was (some may say regrettably) not the only author to pen poetry dedicated to the dessicated dead of Egypt.

Significant literary references to mummies in English, as opposed to those in treatises on medicine and other scientific and philosophical works, begin to appear in the seventeenth century. Perhaps the most familiar are those in Shakespeare; Macbeth's “Witches mummy, maw and gulf”, Othello's handkerchief “died in mummy”, and The Merry Wives of Windsor's Falstaff envisaging his drowned corpse as “a mountain of mummy”. There are also references in Webster's The Duchess of Malfi and The White Devil, in the works of Beaumont and Fletcher, Shirley and others, and one of Donne's poems, Love's Alchemy. What all of these shared, however, was that they referred to the commodity of mummy, traded for use by apothecaries.1

This was understandable, since although people would have been aware of the ultimate source of medicinal mummia, and portions of mummies were kept as curiosities, entire mummies were rare. As an agent for the Turkey Company John Sanderson shipped six hundred pounds of mummy back to England from Egypt in 1586-

This was understandable, since although people would have been aware of the ultimate source of medicinal mummia, and portions of mummies were kept as curiosities, entire mummies were rare. As an agent for the Turkey Company John Sanderson shipped six hundred pounds of mummy back to England from Egypt in 1586-

Literary references to mummies, while still sporadic, continued throughout the seventeenth century, and began to focus more on mummies as preserved people rather than raw material for remedies. John Dryden, in the prologue to his 1668 play Albumazar, a revival of an earlier work by Thomas Tomkis about a celebrated Muslim astrologer, seems to complain bitterly (and perhaps somewhat surprisingly given his use of Tomkis's work) about plagiarists “such authors… as make whole plays, and yet write scarce one word”, complaining that they were worse than highwaymen, since they

“… scarce the common ceremony use

Of, Stand, sir, and deliver up your Muse;

But knock the Poet down, and, with a grace,

Mount Pegasus before the owner's face.”

Even worse, highwaymen

“… strip the living, but these rob the dead;

Dare with the mummies of the Muses play,

And make love to them the Egyptian way; 30

Or, as a rhyming author would have said,

Join the dead living to the living dead.”

Dryden's reference to mummies was still a metaphorical one, but in 1705 the surgeon Thomas Greenhill published his Nekrokedeia, a work on embalming which reflected the religious emphasis of the time on maintaining the body intact for eventual resurrection, and drew on funeral ceremonies and methods of preserving dead bodies from around the world, especially Ancient Egypt. It included an allegorical frontispiece, which Greenhill explained in accompanying verse. In this, he referred to

“Aspiring pyramids, that lift on high

Their spiral heads to reach his kindred sky,

Which in their dark repositories keep

The bodies safe in their immortal sleep;

While healing balm and aromatic spice,

Death's odious dissipation to their form denies.”

The beginning of the nineteenth century saw Napoleon's expedition to Egypt, and the resulting escalation of contact between Europe and Egypt, and of interest in Ancient Egypt and its surviving artefacts. Not only were more complete mummies, and their coffins, shipped back to Europe, but they began to be exhibited to the general public (at least to those who could afford the entry fees) rather than just a social and cultural elite. One of the earliest, and also most celebrated of these exhibitions, was Giovanni Belzoni's 1821 display of his copies of reliefs from the tomb of Sety I at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, and in a promotional event before this, Belzoni unrolled a mummy. Thomas Pettigrew, who went on to become the mummy unroller par excellence of his day, was present at this, and mentioned it in the introduction to his pioneering A History of Egyptian Mummies, but the event also called to the literary muse in Horace Smith.

The beginning of the nineteenth century saw Napoleon's expedition to Egypt, and the resulting escalation of contact between Europe and Egypt, and of interest in Ancient Egypt and its surviving artefacts. Not only were more complete mummies, and their coffins, shipped back to Europe, but they began to be exhibited to the general public (at least to those who could afford the entry fees) rather than just a social and cultural elite. One of the earliest, and also most celebrated of these exhibitions, was Giovanni Belzoni's 1821 display of his copies of reliefs from the tomb of Sety I at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, and in a promotional event before this, Belzoni unrolled a mummy. Thomas Pettigrew, who went on to become the mummy unroller par excellence of his day, was present at this, and mentioned it in the introduction to his pioneering A History of Egyptian Mummies, but the event also called to the literary muse in Horace Smith.

Horace, and his elder brother James, were the initially anonymous authors in 1812 of Rejected Addresses. Purporting to be a selection of odes unsuccessfully submitted to a competition for an address to be delivered on the reopening of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, they were in fact accurate and often amusing parodies of leading poets of the day, including Wordsworth, Coleridge and Byron. Written in only six weeks, the title went through at least fifteen editions, but James only dabbled in literature thereafter. Horace, however, having made a fortune as a stockbroker despite “being from his youth upward better known at Parnassus [home of the Muses] than in the vicinity of the [Stock] Exchange”, in the words of an obituary in The Art-

Unsurprisingly, the poem (the full text of which can be read by following the link above to Bartleby.com) is a monologue in which Smith questions the mute mummy on its knowledge of history while alive, both Egyptian and earlier, whether in its tomb it was aware of foreign conquerors, Persian and Roman, and attempts to persuade it to disclose personal details such as its “name and station, age and race” before finally giving up and drawing a suitably pious moral on the pointlessness of preserving the body whilst ignoring the needs of the soul

Unsurprisingly, the poem (the full text of which can be read by following the link above to Bartleby.com) is a monologue in which Smith questions the mute mummy on its knowledge of history while alive, both Egyptian and earlier, whether in its tomb it was aware of foreign conquerors, Persian and Roman, and attempts to persuade it to disclose personal details such as its “name and station, age and race” before finally giving up and drawing a suitably pious moral on the pointlessness of preserving the body whilst ignoring the needs of the soul

“Why should this worthless tegument endure,

If its undying guest be lost for ever?

O, let us keep the soul embalmed and pure

In living virtue, that when both must sever,

Although corruption may our frame consume,

The immortal spirit in the skies may bloom!”

Earlier poets, in the seventeenth century, had used the commodity of mummy as a negative metaphor, its unnatural and unattractive preservation used to suggest that, to adapt Shakespeare's phrase, something was rotten in not only the state but family and personal relationships. In Greenhill's explanation of the frontispiece to Nekrokedeia, a change in emphasis can be seen. He spoke of it illustrating “how mortal man seeks immortality”, but how

“His beauteous frame he sees with speed decline,

And soon dissolved by death, tho' form'd by hands divine”

The reference to plural “hands” was reinforced by numerous other allusions to Classical pagan culture. He speaks of how Man “disdaining death, strives to extend his name”, and of how

“Temples and fanes they to the Godhead raise,

To bribe the only Power, that can destroy, with Praise”

Although in the singular, this can at best be read as an indirect reference to the Christian god, as he goes on to explain how

“Jove pleas'd, in pity of the pious race,

Two messengers sends down the Airy space,

To raise Man's ashes from the silent Urn,

Which touched by Hermes wand resume their pristine Form.

Jove's Royal Bird attends to bear on high,

Th'Immortal Soul up to its Native Sky”

Later poets also tended to concentrate on the preservation of identifiable individuals, but where spiritual survival was mentioned this was more likely to be linked to specifically Christian religious beliefs in judgement and resurrection.2 Addressing his mummy, Smith pronounced

“Thou wilt hear nothing till the Judgement morning,

When the great trump shall thrill thee with its warning.”

At around the same time that Smith was writing, the American poet William Howe Cuyler Hosmer, in The Memphian Mummy, acknowledged that the female mummy who was the subject of his poem “To Apis or to Isis may have prayed”, but still ended by describing its resurrection in recognisably Christian terms

“When the last trump shall animate the tomb,

And call the dead from out the sea and earth -

Maiden, thy spirit will its dust resume,

Far from thy place of birth.”

Whatever their literary merits, all these poems are interesting for their use of mummies as symbols, and for the way that what they symbolise has changed over time. Significantly, one thing all of them have in common is little if any connection to the original role and symbolism of mummies in Ancient Egypt.

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

1. See Schwyzer, Philip 'Mummy is Become Merchandise: Literature and the Anglo-

2. See Day, Jasmine 'The Mummy Speaks' and 'The Maid and the Mummy'.

September 2015

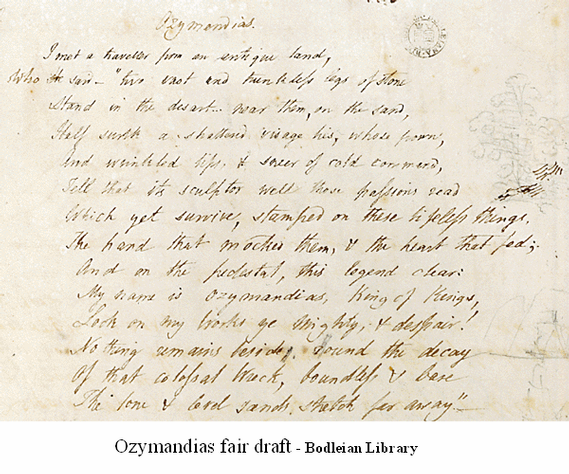

Stanzas on Stones

On Boxing Day 1817, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and his wife Mary welcomed Horace Smith to their house at West Street in Marlowe, Buckinghamshire, where he was to be their house guest for several days. Smith was not only a friend of Shelley, but helped to manage the poet's financial affairs. As part of their entertainment over the holiday period, the two men engaged in a poetry competition, in which each had to write a sonnet on a chosen subject within a fifteen minute time limit. (A sort of poetic equivalent of speed chess.) The relatively short fourteen line sonnet form was ideal for this.

Each of the resulting poems quoted at their beginning, in almost identical form, a passage from the writings of the classical Roman author Diodorus Siculus, which can be taken as their inspiration. The passage was one in which Diodorus described a colossal statue of Ramses II at Thebes, and particularly the inscription on it1

‘I am Osymandyas, king of kings; if any would know how great I am, and where I lie, let him excel me in any of my works.’

(The name, usually spelt as Ozymandias, is generally believed to be a Greek form of the throne name of Ramses II, 'User-

The Younger Memnon

The subject chosen for the poems was a topical one. Interest in Ancient Egypt had been fuelled by the arrival in London in 1802 of Egyptian antiquities, including the Rosetta Stone, and the publication of an English translation of Vivant Denon's account of his travels in Egypt with the French army and of the surviving monuments of Ancient Egypt. Now, the arrival of the so-

The Lover and the Leg

Both poems were published in The Examiner soon after they were written. Shelley's appeared first, on 11th January 1818, under the pen name 'Glirastes'. (Translating as 'Dormouse Lover', this was a private joke, based on his pet name for Mary Shelley 'Dormouse'.) Smith's was published a month later, on 1st February, under the initials 'H.S.'. The Examiner had been founded ten years earlier by John Hunt as a liberal political counterpart to more conservative journals and was edited by his brother Leigh, who knew Shelley well, and introduced him to his fellow poet John Keats. Both poems were also republished, Shelley's in 1819, in his collection Rosalind and Helen, Smith's in 1821 in his Amarynthus. Shelley kept the title Ozymandias. Smith renamed his sonnet On A Stupendous Leg of Granite, Discovered Standing by Itself in the Deserts of Egypt, with the Inscription Inserted Below. It is hardly surprising, given this, that of the two poems it is Shelley's that is best known nowadays. To be fair to Smith, his retitling of his poem may have had an element of irony in it. He and his brother James had come to fame with their Rejected Addresses, parodies of the leading poets of the day, and if his version of Ozymandias lacks Shelley's technical sophistication, its theme and tone are still similar. Leaving aside the relative literary merits of the two poems, however, they are interesting for what they suggest about the way in which Ancient Egypt was perceived at this time.

The Wilderness where London stood

Champollion's final decipherment of hieroglyphs was still several years away, and Classical sources of information on Ancient Egypt, such as Diodorus and Strabo were still of paramount importance. Both poets used the archaic spelling 'desart' for 'desert' in their poems (although it is normally modernised now in Shelley's), which reflected the use of these sources, and the fact that even to their authors Egypt was already ancient, emphasising the antiquity of Egypt. In both poems the statue serves to emphasise the transient nature of temporal power, even for rulers as mighty as the Pharaohs of Egypt, and in Smith's case he speculated that their own civilisation might suffer the same fate as that of the Pharaohs. The choice of topic for the sonnet competition reflected the contemporary interest in Egyptian antiquities, as well as the debate over the rival artistic merits of Greek and Egyptian sculpture, and by extension the respective cultures that produced them. Shelley was soon to leave England, and never returned, but before he did he went on to write a sonnet to the Nile, again as part of a sonnet competition, this time with John Keats and Leigh Hunt, and Smith was also to write Address to the Mummy at Belzoni's Exhibition and To the Alabaster Sarcophagus in 1821, the latter referring to the sarcophagus of Sety I, initially deposited in the British Museum, but now in Sir John Soane's Museum.

Even today, the image of the ruined colossus of Ozymandias still retains its power, and gave its name to an episode of the crime drama Breaking Bad, where the poem was recited in its entirety. Perhaps the last words should belong to Smith and Shelley, however.

Ozymandias

I met a traveller from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert… Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Percy Bysshe Shelley

Ozymandias

IN Egypt's sandy silence, all alone,

Stands a gigantic Leg, which far off throws

The only shadow that the Desart knows:—

"I am great OZYMANDIAS," saith the stone,

"The King of Kings; this mighty City shows

"The wonders of my hand."— The City's gone,—

Nought but the Leg remaining to disclose

The site of this forgotten Babylon.

We wonder,—and some Hunter may express

Wonder like ours, when thro' the wilderness

Where London stood, holding the Wolf in chace,

He meets some fragment huge, and stops to guess

What powerful but unrecorded race

Once dwelt in that annihilated place.

Horace Smith

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

1 See British Library web site 'An Introduction to Ozymandias'

2 James, The British Museum and Ancient Egypt p. 10

October 2015

Apart from Tony and Cleo…

There are plenty of films that evoke Ancient Egypt, and even Egyptian style cinemas that showed them, but what plays can you think of with an Ancient Egyptian theme? Apart from Shakespeare's Anthony and Cleopatra, of course, and even that was set in late Ptolemaic Egypt. A previous newsletter (August 2015), touched on some plays that mentioned mummy as medicine, but these were isolated references, in plays whose setting and themes were a long way from Egypt. In the late eighteenth century the Theatre Royal Drury Lane hosted The Fall of Egypt by John Hawkesworth, but this was an oratorio based on the biblical account of the Exodus, where the religious message was the focus rather than the culture of Ancient Egypt.

Battles and Bombardments

Unsurprisingly, the catalyst for Egyptian dramas was Napoleon's expedition to Egypt between 1798 and 1801. As early as March 11th 1800, the third incarnation of the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, London hosted The Egyptian Festival, a three act opera with music by Charles Florio and libretto by Andrew Franklin. It featured choruses of priests, women, and Mamelukes, and according to a contemporary account it concluded with the bombardment of a fort, filling the theatre with suffocating smoke. The scenery was commented on positively, although reviews otherwise seem to have been poor, but the focus seems to have been firmly on topical events, following Nelson's victory at the Battle of the Nile, and anticipating Sir Ralph Abercromby's victory at the Battle of Alexandria. In 1801, Sadler's Wells theatre staged Egyptian Laurels, which included a representation of the Battle of Alexandria, and a musical segment by Charles Dibdin, the songwriter and theatrical entrepreneur who was soon to take over the Wells, entitled Death and Apotheosis of Sir Ralph Abercromby. The great comic actor of his day, Joseph Grimaldi, appeared in it as an Irish character called O’Doody, and compared “English and Egyptian Wonders, including Mamelukes and St Luke’s, Pyramids and Obstacles, Crocodiles and Monopolists, Mummies and Men Milliners, the Fortunes of War and Peace, etc. etc.”. In July 1806, the Wells put on the pantomime Anthony, Cleopatra and Harlequin which seems to have been a revival of an original production in 1803. In it, Grimaldi performed “the Original Mummy Dance”, which he had composed, and there were scenes representing “the Interior of an Egyptian Catacomb, with the tomb of Nilus…the splendid barge in which Cleopatra sailed to meet Mark Anthony [and a] view near Alexandria”. There were also, with the splendid eclecticism of pantomime, scenes set in Greek temples in the Aegean, Lapland (with Grimaldi doing a dance in snow shoes), an English kitchen, a Chinese garden and pagoda, the banks of the River Wye in Herefordshire by moonlight, and a Magic Palace.

Patagonians, Panoramas and Politics

Around the same time, Giovanni Battista Belzoni, later to achieve fame as a traveller and pioneer Egyptologist, was appearing in theatres in London and elsewhere around the country. In early 1804 the Royalty Theatre in Well Street (now Ensign Street) not far from the Tower of London put on its annual pantomime, which that year was called The Egyptian Oracle; or Harlequin’s Punishment. There is no direct evidence that Belzoni was involved in it, although he did appear in other pantomimes, and at this time he was known for his feats of strength as The Patagonian Sampson and theatrical hydraulics, but it is tempting to speculate on how much the enthusiasm for entertainment with an Egyptian theme played its part in influencing the course of Belzoni’s future career.

Around the same time, Giovanni Battista Belzoni, later to achieve fame as a traveller and pioneer Egyptologist, was appearing in theatres in London and elsewhere around the country. In early 1804 the Royalty Theatre in Well Street (now Ensign Street) not far from the Tower of London put on its annual pantomime, which that year was called The Egyptian Oracle; or Harlequin’s Punishment. There is no direct evidence that Belzoni was involved in it, although he did appear in other pantomimes, and at this time he was known for his feats of strength as The Patagonian Sampson and theatrical hydraulics, but it is tempting to speculate on how much the enthusiasm for entertainment with an Egyptian theme played its part in influencing the course of Belzoni’s future career.

A more serious approach to Egypt was taken at the Lyceum Theatre, probably in 1801 or 1802 (sources differ), where Mark Lonsdale's Aegyptiaca was staged. Lonsdale’s production was in three parts, on the Arts, Manners and Mythology of Ancient Egypt, Modern Egypt, and Society and Manners in Modern Egypt. It began with eighteen large pictures based on Vivant Denon’s Description de l’Égypte, and short accompanying descriptions, written and delivered by the writer and diarist John Britton, and was a precursor of the later panoramas of Egypt, especially the Nile Panorama in which Joseph Bonomi was heavily involved. Sadly, in the words of the nineteenth century playwright and theatre historian Charles Dibdin Jr., “…from its possessing a character too chastely classical to become popular, it entirely failed of success.” and Lonsdale was ruined. Even the more successful Nile Panorama, exhibited in 1849 in the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly, was to encounter financial problems, and the overall emphasis on theatrical treatments of Egypt was firmly focussed on entertainment.

1811 saw the first London production at the Haymarket Theatre of Mozart's The Magic Flute, with its Masonic and Egyptian elements, but a fantasy setting. More firmly connected to Egypt was an 1817 production at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, “A New MUSICAL DRAMA in three acts which has been long in preparation, called ELPHI BEY: or, The ARAB’S FAITH”, written by Ralph Hamilton, with music by Thomas Attwood (a pupil of Mozart’s) and others. Hamilton’s introduction credited Henry Salt, British Consul in Egypt at the time, for the story that inspired it, and Salt's illustrations to Viscount Valentia’s Voyages and Travels… to Egypt as the principal inspiration for the scenery. It was even described by Hamilton as a “joint composition”, although there is no direct evidence that Salt wrote any of it.

The story was a romanticised version of an incident involving Elphi Bey recounted in Valentia's book, which took part during the long and complex civil war in Egypt resulting from the power vacuum created by the French defeat at the Battle of the Pyramids of the Mamelukes, the ruling military caste of Egypt at that time. Elphi (or Elfi) Bey, more properly Muhammed Bey al-

The story was a romanticised version of an incident involving Elphi Bey recounted in Valentia's book, which took part during the long and complex civil war in Egypt resulting from the power vacuum created by the French defeat at the Battle of the Pyramids of the Mamelukes, the ruling military caste of Egypt at that time. Elphi (or Elfi) Bey, more properly Muhammed Bey al-

Mummies and Monotheism

These early nineteenth century productions can be attributed to the general enthusiasm for all things Egyptian in the Regency period, but, even if they were not numerous, such entertainments continued to occur beyond it. In 1824, the Theatre Royal Covent Garden staged Charles Farley's The Spirits of the Moon; or the Inundation of the Nile, and in 1833 William Bayle Bernard's one act farce The Mummy entertained audiences at the Adelphi Theatre in the Strand with a lover in disguise, an actor pretending to be a mummy, his father selling a real mummy, the Elixir of Life rediscovered by the beloved's father, a bottle of brandy, a sarcophagus, switched labels and confusion between them all with, as the time-

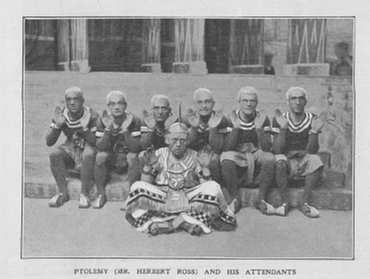

The turn of the Twentieth Century saw the New and Criterion Theatres play host to Amasis: an Egyptian Princess, a comic opera in two acts, based on a passage from the writings of Diodorus Siculus about a Roman lynched for killing a cat in Egypt. The action sees the poor scribe Cheiro, in love with Princess Amasis, condemned to death for confessing to killing a sacred cat actually killed accidentally by the princesses's suitor Prince Amhotep. Eventually, Cheiro is saved by the princess, the lovers united, and the scheming Court Embalmer and Private Secretary to Pharaoh, Ptolemy Theopompus Allakama, who has plotted to kill Amhotep to inherit his wealth, is mummified in his own patent embalming machine. Among its delights were a dance by “Mummy Guards”. Romance and adventure, rather than mummies, seem to have been the key elements of Secret Egypt, staged in 1928 at the Q Theatre at Kew Bridge. It was co-

The turn of the Twentieth Century saw the New and Criterion Theatres play host to Amasis: an Egyptian Princess, a comic opera in two acts, based on a passage from the writings of Diodorus Siculus about a Roman lynched for killing a cat in Egypt. The action sees the poor scribe Cheiro, in love with Princess Amasis, condemned to death for confessing to killing a sacred cat actually killed accidentally by the princesses's suitor Prince Amhotep. Eventually, Cheiro is saved by the princess, the lovers united, and the scheming Court Embalmer and Private Secretary to Pharaoh, Ptolemy Theopompus Allakama, who has plotted to kill Amhotep to inherit his wealth, is mummified in his own patent embalming machine. Among its delights were a dance by “Mummy Guards”. Romance and adventure, rather than mummies, seem to have been the key elements of Secret Egypt, staged in 1928 at the Q Theatre at Kew Bridge. It was co-

Theatre is about many things, but ultimately it can be argued that even 'serious' theatre is about entertainment in the widest sense. While these plays may tell us little about Ancient Egypt, and what they do tell us is seldom accurate, they do tell us a lot about our perception of it. Topical productions, especially spectacular ones, are popular but by definition largely about the Egypt of their day. What keeps appealing to audiences is not real Ancient Egypt, but fantasy Egypt, a land of monuments, magic, mummies, and the mysterious Queen Cleopatra. Which means, of course, that we cannot forget the fantasy Moorish style Alhambra Theatre and others which were the setting from the late 1920s to the early 1960s for Cleopatra's Nightmare and the Sand Dance of the immortal Wilson, Keppel and Betty.

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

November

Against the Grain

“My own personal theory is that Joseph built the pyramids in order to store grain”.

The opening words of a video clip from a speech by the US presidential candidate Ben Carson, and ones which did little to help his campaign. To be fair, the speech from which it was taken, to graduating students at Andrews University in Michigan, had been made nearly eighteen years before, in 1998, but when he was contacted by CBS News, after the clip had been posted by the Internet news site Buzzfeed on 4th November 2015, he confirmed that “It's still my belief, yes.”1 Even Daniel Weber, a spokesman for the Seventh Day Adventist Church of which Carson is a member, described the theory as “his [Carson's] own interpretation [of biblical scripture]”.2 Now, there have been plenty of Egyptologists to explain, as patiently and positively as they can manage, on exactly what basis they believe that the Egyptian pyramids were funerary rather than agricultural in function, so that's not what this issue of the newsletter is about. It's not even about the views of Dr Carson. He is welcome to believe whatever he likes, as long as he doesn't try to impose those views on others, and he did emphasise that it was a personal belief. Rather, it is a response to the surprising comments with which the Adventist spokesman Daniel Weber followed his metaphorical swift step back from Carson's views. Weber went on to say:

“Of course we [Seventh Day Adventists] believe in the biblical account of Joseph and the famine, but I've never heard the idea that pyramids were storehouses of grain.”

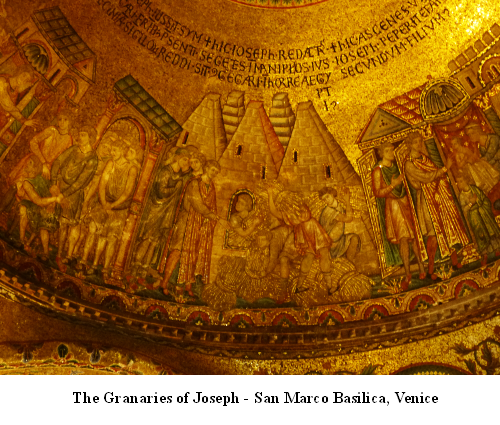

This is a bit surprising, given how far back belief in the Pyramids of Giza as the Granaries of Joseph goes. In an article on the BBC web site3, Professor John Darnell, of Yale University, refers to the thirteenth century mosaics in the narthex of the Basilica of San Marco in Venice which illustrate the biblical story of Joseph and his brothers, and show the Pyramids as granaries. The article goes on to quote the 6th century AD St Gregory of Tours, who wrote:

“And on its [the Nile's] bank is situated, not the Babylonia of which we spoke above, but the city of Babylonia in which Joseph built wonderful granaries of squared stone and rubble. They are wide at the base and narrow at the top in order that the wheat might be cast into them through a tiny opening, and these granaries are to be seen at the present day.”4

Gregory spent his life in what is now France, and so could not have written from first-

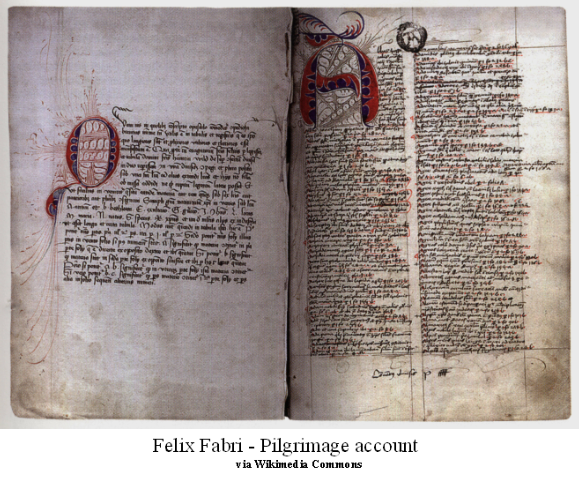

Pilgrims and Pharaohs