April

Here be dragons…

We all know what medieval cartographers did when they came to areas of the globe of which they knew little other than the fantastic tales of travellers. They left them blank apart from the cautionary text ‘Here be dragons..’. Except that they didn’t. Apart, it seems, from one exception.

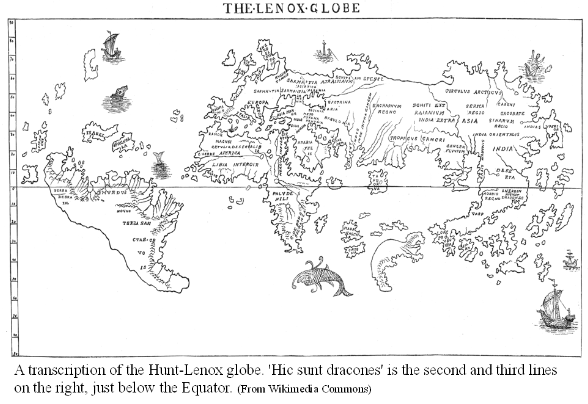

The so-called Hunt-Lenox globe dates to the early sixteenth century, around 1510, and is one of the earliest European globes. It may be a cast in copper of an earlier globe from around the same time, carved on two half ostrich eggs glued together, and both globes bear the Latin text, in the area depicting south-east Asia, ‘Hic sunt dracones’ - Here there are dragons. (It has been speculated, based on the text’s location on the globes, that this is a reference to tales of Komodo Dragons from Indonesia.) They also appear to be the only ones with this text. Other medieval maps and globes show frolicking sea monsters and strange beasts, but not the classic phrase.[1]

However, we may still be able to find dragons on them. Medieval mappa mundi (maps of the world) are very differently laid out from modern maps, and are not what we would consider geographically accurate, but on one of them, the thirteenth century Ebstorf Map, a section corresponding to part of southern Africa showed several cocatrices. These were mythical beasts, resembling two legged dragons, supposedly hatched by a serpent from the egg of a cock, and with a deadly gaze or touch. So far, so mythical, but in the account of his pilgrimage to the Holy Land by the fourteenth century Irish Franciscan Symon Semeonis, he described his passage along the Nile, in which river could be found a highly noxious animal, resembling the dragon, which devoured both men and horses, and which was commonly called a ‘cocatrix’ (i.e cocatrice). This, of course, was Crocodylus niloticus, the Nile Crocodile. The fifteenth century Castilian traveller Pero Tafur also mentions them, calling them “cocatriz”.

How doth the little crocodile…

Nile crocodiles were well known to the Romans. Pliny describes them in his Natural History (Book VIII Chapter 37), and they were also mentioned by Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus. Strabo mentions Souchos the crocodile god, and a papyrus found in a crocodile mummy at Tebtunis in Egypt indicates that during the visit to Egypt of the Roman senator Lucius Memmius he fed tidbits to the sacred crocodiles at the temple of Sobek.[2] Crocodiles, and images of them, were not always confined to Egypt, either. Cassius Dio tells us that crocodiles were sacrificed in Rome after the dedication of the Forum of Augustus, and they are shown in the so-called Nilotic mosaics in Italy which depict Egypt, including one in the Casa del Fauno at Pompeii, and in the Palestrina Mosaic. (Not everyone recognises them as crocodiles. There are those who claim the mosaics as evidence that humans and dinosaurs were created at the same time and have co-existed.[3])

On his way to the Holy Land via Egypt, the fifteenth century German pilgrim Arnold von Harff visited Rome. There, in the church of Santa Maria in Campitelli he saw what was said to be the skin of a dragon hanging in chains, which he believed “until I found it to be a lie”. Once in Egypt, he recognised it for what it was, a crocodile skin. A trade in crocodile skins had certainly been going on for at least sixty years, and probably a lot longer, as Pero Tafur, who travelled to Egypt from Venice, mentions seeing in the porticoes of the Doge’s palace “some skins of the beasts called crocodiles which the Sultan of Egypt sent as things most monstrous to the Seigniory.” He also mentions one of the two famous columns in the Piazzetta, not the one with the winged lion of St Mark, but the other with its statue that he describes as being “of Saint George with the Dragon”.[4] The beast in question, which looks unslain but suitably cowed, has a dog-like head and stubby wings, but otherwise looks remarkably like a crocodile. The identity of the saint standing on his back is also less clear-cut than it seems from Tafur.

The patron saint of Venice is, of course, Saint Mark, but he was not its first. Originally, Venice was firmly within the sphere of influence of Byzantium, and its first patron saint was Theodore of Amasea, particularly revered as a warrior saint and martyr in the eastern Christian church. Theodore was believed to have been a Roman soldier, as was Saint George, also a martyr, but depictions of Theodore slaying a dragon pre-date the earliest representations of George and the Dragon by at least a century.[5] The statue of Theodore on the pillar in the Piazzetta was not brought to Venice until the early thirteenth century, after the sack of Constantinople in the Fourth Crusade, and is actually not a single piece, but a composite statue created from sculptural fragments brought back from Constantinople. (The arm of Saint George was an important relic also acquired by Venice in the sack of Constantinople, and kept in the Basilica of San Marco, which helps to explain how pilgrims like Tafur came to identify the statue as that of Saint George, rather than Saint Theodore.) The iconographies of Saints Theodore and George and the Archangel Michael share the key elements of an armoured military figure (here on foot, but often represented as a horseman) defeating a reptilian monster, and these elements also suggest a common origin for all three.

Hawk the Slayer

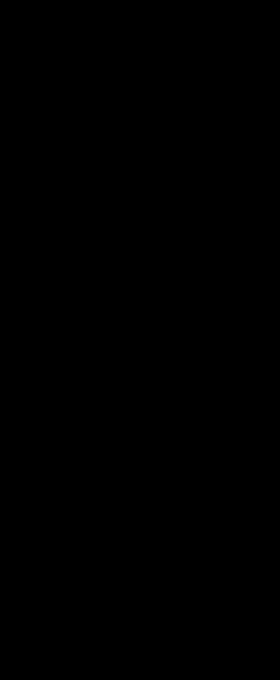

We are familiar with the Ancient Egyptian image of Horus spearing or harpooning a hippopotamus, representing the forces of chaos, and among the contents of the tomb of Tutankhamun was a small wooden statue showing him in the same pose. Hippopotami are not crocodiles, but the magical stelae particularly popular in the Ptolemaic period, known collectively as Cippi of Horus, show the youthful god grasping poisonous snakes and standing on crocodiles. Later, when Egypt was a Roman province, there are representations of a falcon-headed Horus in the armour of a Roman legionary, and one in particular in the Louvre Museum, dating from Coptic Egypt, shows Horus in armour, mounted on a horse, and spearing a crocodile.[6] It is also significant that the Coptic name for Saint George is Abu Girg, and ‘Girg’ means ‘the harpooner’.[7] It is easy to see how a number of warrior saints became associated with this imagery, and how the crocodile became a dragon, representing the forces of darkness and paganism. We know of the crocodile skins in Venice, which may have been recognised for what they were, but we also know from Von Harff’s account about the one displayed as the skin of a dragon in Rome, and that they were sold as such elsewhere in Europe, where they may also have been described as dragon skins, helping to reinforce belief in dragon-slaying saints.

We are familiar with the Ancient Egyptian image of Horus spearing or harpooning a hippopotamus, representing the forces of chaos, and among the contents of the tomb of Tutankhamun was a small wooden statue showing him in the same pose. Hippopotami are not crocodiles, but the magical stelae particularly popular in the Ptolemaic period, known collectively as Cippi of Horus, show the youthful god grasping poisonous snakes and standing on crocodiles. Later, when Egypt was a Roman province, there are representations of a falcon-headed Horus in the armour of a Roman legionary, and one in particular in the Louvre Museum, dating from Coptic Egypt, shows Horus in armour, mounted on a horse, and spearing a crocodile.[6] It is also significant that the Coptic name for Saint George is Abu Girg, and ‘Girg’ means ‘the harpooner’.[7] It is easy to see how a number of warrior saints became associated with this imagery, and how the crocodile became a dragon, representing the forces of darkness and paganism. We know of the crocodile skins in Venice, which may have been recognised for what they were, but we also know from Von Harff’s account about the one displayed as the skin of a dragon in Rome, and that they were sold as such elsewhere in Europe, where they may also have been described as dragon skins, helping to reinforce belief in dragon-slaying saints.

Whilst Saint Theodore was, and still is, revered by the Eastern Christian churches, he was less well known in western Europe, but the cult of Saint George became well established, possibly because of its adoption by Crusaders who spread it on their return, including those from England. Unlike saints whose veneration, and the miracles associated with them, were linked to specific sites, George had no special centre in England, which helped him to become widely adopted there, eventually of course becoming the country’s patron saint. It is strange to think, however, that when we look at George and the Dragon on a pub sign, we may actually be seeing Horus and the Crocodile. Here be dragons indeed.

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

1. Blake, Erin C. (1999). "Where Be "Here be Dragons"?". MapHist Discussion Group.

2. http://tebtunis.berkeley.edu/exhibit/drathbone/1

3. http://www.genesispark.com/palestrina-mosaic-page/

4. All Tafur quotes from: Letts, Malcolm, trans. & ed. The Pilgrimage of Arnold von Harff London, Hakluyt Society 1946.

5. Kuehn, Sara: The Dragon in Medieval East Christian and Islamic Art (2011).

6. Desroches-Noblecourt, Christiane Gifts from the Pharaohs Flammarion 2007 pp. 82-99

7. Anthony Sattin The Pharaoh’s Shadow Indigo 2001 p. 197

See also: https://reliquarian.com/2013/03/23/saint-theodore-warrior-saint-and-dragon-slayer/

We are familiar with the Ancient Egyptian image of Horus spearing or harpooning a hippopotamus, representing the forces of chaos, and among the contents of the tomb of Tutankhamun was a small wooden statue showing him in the same pose. Hippopotami are not crocodiles, but the magical stelae particularly popular in the Ptolemaic period, known collectively as Cippi of Horus, show the youthful god grasping poisonous snakes and standing on crocodiles. Later, when Egypt was a Roman province, there are representations of a falcon-

We are familiar with the Ancient Egyptian image of Horus spearing or harpooning a hippopotamus, representing the forces of chaos, and among the contents of the tomb of Tutankhamun was a small wooden statue showing him in the same pose. Hippopotami are not crocodiles, but the magical stelae particularly popular in the Ptolemaic period, known collectively as Cippi of Horus, show the youthful god grasping poisonous snakes and standing on crocodiles. Later, when Egypt was a Roman province, there are representations of a falcon-