Egypt in England Newsletter

2016

January

Injury and Induration

Cleopatra was famously supposed to bathe in asses' milk for the benefit of her complexion, and when the Needle named after her came to London, there was considerable concern for its complexion, but for a different reason. The Needle was coming to an already crowded city expanding so fast that it resembled one great building site, heated by coal fires and lit by coal gas, and still thick with industry. Its legendary fog, the 'London Particular', was actually a toxic smog, described in 1820 by the artist and engraver John Sartain as

“a compound from the effusions of gas pipes, tan yards, chimneys, dyers, blanket scourers, breweries, sugar bakers, and soap boilers”

Annals of the fine arts. London, 1820, Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, p. 80

Only two years after the obelisk had been erected, another writer described its effects

“A white cloth spread out on the ground rapidly turns dirty, and particles of soot attach themselves to every exposed object.”

Hon. F A R Russell, London Fogs (London: 1880), p. 6.

Over the decades since the first proposal to transport the obelisk to England, one of the factors that had delayed its arrival was the belief that it had been so badly damaged that it would not be worth the expense of bringing it to England. Once it was clear that the obelisk was finally coming to London, however, concern over its condition was replaced by concern over its survival. In February 1878 The Times fretted that

“At every site suggested, the Obelisk would be covered with a thick coating of coal smut in ten years, and the hieroglyphics would have to be picked out – dug out, one may say – with sufficiently hard instruments in the hands of common workmen. That destructive process, accompanied with washing – perhaps a still more destructive process – has had to be repeated several times even on the sculptures of the Albert Memorial. The Obelisk would soon be as dark and unmeaning as a chimney-

The Times Feb 1 1878 p. 10

In March of the same year, in the House of Lords, the Duke of Somerset noted

“A statement which had been made that unless the hieroglyphics on Cleopatra's Needle were preserved by some process, they would be obliterated by the effects of the smoke of London.”

Hansard: HL Deb 07 March 1878 vol. 238 c826

He asked the Lord President of the Council, the Duke of Richmond and Gordon, if he would take

“the opinion of scientific men as to the best mode of preserving the inscriptions from the destructive effects of the London atmosphere”

Hansard: Ibid

The Duke of Somerset suggested glazing the Needle, “or other mechanical means”, and the Lord President assured him he would “take immediate steps to make enquiries”. This might have been a classical politician's prevarication, but by August, although the Needle was still horizontal

“A portion of the pyramidion has been washed and coated with a solution composed, it is stated, of beeswax dissolved in spirits of wine. Its application has had the effect of showing the roseate colour of the granite, and the tone of the small portion of the obelisk so treated is in pleasing contrast with the dirty grey aspect of the monolith generally.”

Illustrated London News August 10 1878 p. 133.

After an initial cleaning of the whole obelisk, it was treated in 1879 with two coats of Browning's Invisible Preservative, a solution of Dammar resin (a type of varnish) and wax in petroleum spirit, under the supervision of its inventor, Henry Browning. Not long after this, Browning must have sold his formula to the splendidly named Indestructible Paint Company, as “The solution applied to the stone of Cleopatra's Needle—the Indestructible Paint Company's stone solution” is mentioned in Parliament on 5th May 1885 in connection with the treatment of stonework in Westminster Hall. Despite the initial treatment, in 1890 Mr Conybeare MP asked the Home Secretary if

After an initial cleaning of the whole obelisk, it was treated in 1879 with two coats of Browning's Invisible Preservative, a solution of Dammar resin (a type of varnish) and wax in petroleum spirit, under the supervision of its inventor, Henry Browning. Not long after this, Browning must have sold his formula to the splendidly named Indestructible Paint Company, as “The solution applied to the stone of Cleopatra's Needle—the Indestructible Paint Company's stone solution” is mentioned in Parliament on 5th May 1885 in connection with the treatment of stonework in Westminster Hall. Despite the initial treatment, in 1890 Mr Conybeare MP asked the Home Secretary if

“he has noticed the extent to which the action of the weather has corroded Cleopatra's Needle so that many of the hieroglyphics appear to be becoming effaced; and whether any steps can be taken to remedy the mischief?”

The Home Secretary replied that

“in May of last year the acting engineer made an examination as to the condition of the Needle, and reported that its present state was not unsatisfactory; that the surface of the stone does not seem to have been affected by the weather to a greater depth than a quarter of an inch, and the hieroglyphics are in many places more than two inches deep. The granite does not seem to have deteriorated since the Obelisk was examined 16 years ago.” [i.e.1874]

Hansard: HC Deb 20 May 1890 vol. 344 c1407

Clearly, others did not feel that this was the case, and the following year a magazine noted that

“It is said that the London atmosphere is having a most disastrous effect upon Cleopatra's Needle, on the Thames Embankment. It has, however, been suggested that a dressing of “silicates” may perhaps save the hieroglyphs from utter effacement.”

Illustrated London News February 28 1891 p. 271.

Whether in response to such concerns, or simply because of fresh deposits of sooty dirt, the Needle was treated again in 1895. It is probably this which is shown in a trade postcard from the Indestructible Paint Company, where it is described as the “induration” or hardening of the obelisk, a term normally used in medical contexts. The Needle was again cleaned and waxed in 1911, and washed by the hoses of the London Fire Brigade in 1932. A pattern thus emerged of cleaning and coating every 16-

“whether the stone shows any signs of decay as the effect of the London atmosphere and climate; and whether any steps are being taken to preserve from gradual destruction this monument?”

Hansard: HC Deb 25 November 1912 vol. 44 cc793-

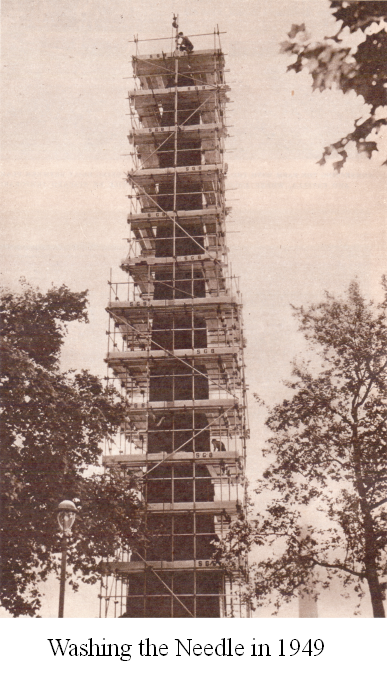

I n 1949, it was claimed that a party of visiting Egyptian VIPs had complained about the state of the Needle1, and that as a result the London County Council spent £500 on a month long cleaning during which it was sprayed, cleaned with a non-

n 1949, it was claimed that a party of visiting Egyptian VIPs had complained about the state of the Needle1, and that as a result the London County Council spent £500 on a month long cleaning during which it was sprayed, cleaned with a non-

Despite all this cleaning and waxing, there were still those who worried about the Needle's safety. In 1984 Dr David Clark MP claimed that due to acid rain

“Cleopatra's needle has lost more detail in 80 years on the Embankment than it lost during the previous 3,000 years in Egypt, despite the harsh climate, the sand and the wind.”

Hansard: HC Deb 08 June 1984 vol. 61 cc554-

A year later David Alton MP quoted an almost identical statement from a letter to him from a constituent.

So are these fears justified? One of the papers presented at an international conference on conservation issues concerning public sculpture and monuments held at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1998 dealt with Cleopatra's Needle, and concluded that although there had been some erosion, it was probably a result of fire damage around 525 BC during the Persian conquest of Egypt.2 The most recent cleaning took place in 2005, and a report by the company who carried it out (and who had also done the 1979 cleaning) concluded that it was in surprisingly good condition for its age, despite some “contour decay” (basically flaking off of the granite surface).

“The contour decay that is occurring is not new, it is in fact part of the natural life cycle of granite [and] Although granite is an extremely durable material, it does not last forever, especially as the obelisk is composed of the weaker syenite granite… To minimise further decay, it is our opinion that some sort of maintenance programme be considered… Steam cleaning the surface to remove pollutant, organic growth and debris would have a beneficial effect on the obelisk if this was carried out on a regular basis.”3

Cleaning London's air would undoubtedly help, but the more apocalyptic predictions about the Needle's decay seem to have been overstated, and with careful treatment it and its inscriptions should be with us for a long time to come. Meanwhile, on the other side of the Atlantic in New York, questions are being asked about the condition of its sister obelisk, and how best to clean and preserve it...

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

1. Adrian Ball Cleopatra's Needle Kenneth Mason 1978 p. 32.

2. Teutonico and Fidler (Eds.) Monuments and the Millennium English Heritage 2001.

3. The Conservation of Cleopatra's Needle Victoria Embankment London July-

February

Pilgrimage to Paradise

What's the most delicious thing you've ever tasted?

Whatever it was, it is unlikely to have been river water, particularly from the River Nile. Those of you who have been to Egypt will be familiar with the saying that “If you drink from the Nile you will come back to Egypt.”, usually trotted out by Egyptians with a sense of humour who encourage you to ensure your return by doing just that. I've always been able to resist the invitation, and it hasn't stopped me going back on numerous occasions. (I would not encourage you to try the same line with tourists to your own area, substituting the name of your local river and your country.)

Reading the accounts of medieval and renaissance pilgrims to Egypt, however, I was struck by passages in which they referred to drinking water from the Nile. Not that it was surprising they did this; in those days it would have been, apart from wells and very rare rainfall, the source of water in Egypt. No, it was the way in which they described its taste.

In 1323 Symon Semeonis, an Irish Franciscan monk, (also known as Simon FitzSimon, Simon Fitzsimons, Simon FitzSimmons or Simon Fitz Semeon) travelled to Egypt on pilgrimage with his colleague, the splendidly named Hugo Illuminator, who sadly died of dysentery in Cairo. In his account, Symon says that the Nile is

“in virtue most efficacious, and most suave, and to drink most delectable, never noxious or offensive but entirely agreeing with human nature.”

Hoade, Western Pilgrims p. 23

Between 1436 and 1438, the Castilian Pero Tafur travelled to Egypt and the Holy Land on pilgrimage. In his account of it, he writes that

“The water of the Nile is the best in the world and seems, in truth, to be water of paradise. During the whole period of my visit I drank nothing but this water, although I could have had excellent wine.”

Letts, Travels of Pero Tafur, p. 70

Around sixty years later, the German nobleman Arnold von Harff similarly wrote of it being

“very healthy… as sweet as can be found in the round world.”

Letts, The Pilgrimage of Arnold von Harff

This, remember, is Nile water that they are talking about. But for them it really was, in Tafur's words, “water of paradise”.

And a river went out of Eden…

Tafur wrote that the Nile “comes down from the terrestrial paradise”, and Symon Semeonis wrote, citing the classical historian Flavius Josephus, that the river was “one of the four that issue from Paradise, and is today named Nile by the Egyptians”. This concept was explained in more detail by Fra Niccolò da Poggibonsi, who travelled through Egypt to Jerusalem between 1346 and 1350. Citing scripture and the Old Testament (Genesis 2.10) as his authorities, he says that

“there flow four rivers from the terrestrial Paradise. The first is called Phison and goes to India and by Civalach; the next is called Tigris and goes by Syria; the third is called Euphrates and goes by Chaldea; and the last is called Gihon and this encompasses Ethiopia and a part of Egypt; this latter is called the Nile and traverses the land of Egypt...”

Bellorini and Hoade A Voyage Beyond the Seas p. 90

In Christian tradition, the Garden of Eden described in the Bible was also referred to as the Terrestrial or Earthly Paradise (as opposed to the Heavenly Paradise), and was believed by many to exist in some suitably distant and exotic location, of which many were suggested. One favourite was the kingdom of Prester John, a legendary Christian king in the East, whose kingdom was widely believed in the 14th century to lie in Ethiopia. Von Harff claimed to have travelled to the source of the Nile in the Mountains of the Moon, and that it flowed to the springs there underground from Paradise, but this part of his narrative, and his claim to have subsequently travelled back down the Nile to Cairo, are clearly fabrications based on the works of other authors.

The fruit of that forbidden tree…

It was not only the water of the Nile which was thought to be associated with paradise. Pilgrims also ate “paradise apples”, which they praised extravagantly. Symon Semeonis said of them

“you should know that the paradise apples, saving a better judgement than mine, among all kinds of apples, hold the first place for incomparable goodness...”

Hoade, Western Pilgrims p. 22

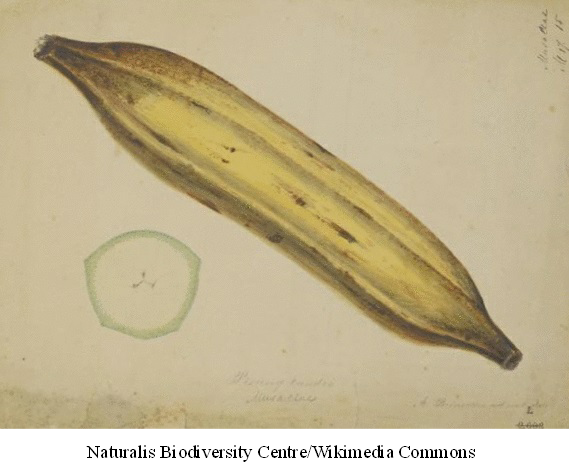

Another pilgrim, a Tuscan called Frescobaldi, said that they were “sweeter than sugar”, and went on to write that “they say it is the fruit in which Adam sinned”, in other words the fruit of the tree in the Garden of Eden which Eve was tempted to eat by the Serpent, and which Adam then ate as well. In illustrations of the biblical account, the fruit is traditionally shown as an apple, but Frescobaldi says that these paradise apples are “like to cucumbers”, and his companion Sigoli, in his account of their pilgrimage, says that “they are in colour like our cucumbers”. Both Frescobaldi and Sigoli also call them 'Muse', which is the crucial clue, and all becomes clear when Semeonis says that

“they are not apples of a tree, but of a plant growing high like a tree, which they call musa”

and adds that they are “oblong and yellow in colour when ripe”. The fruit being referred to, of course, is the banana, which can be any one of a variety of species of the genus Musa. (We tend nowadays to think of cucumbers as exclusively green, but if you think of courgettes and marrows, they can be yellow as well.) To European pilgrims, this exotic fruit, eaten in a country whose river was believed to flow from Paradise itself, must have been easy to identify with the fruit with which Eve was tempted. This would have been reinforced by what they saw as an especially significant feature of bananas. As Frescobaldi explained “dividing it in any way you find a cross”, and Semeonis also noted that they were

“signed with the sign of the crucified, for when they are cut across there appears in them most clearly the image of the crucified as on a cross extended.”

Hoade, Western Pilgrims p. 22

Clearly, their faith helped them to see this resemblance, but just as they could believe that they were drinking water that originated in Paradise itself, they could also believe that the fruit they ate had originally grown there.

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

Bellorini, Fr. Theophilus & Hoade, Fr. Eugene, Trans. Visit to the Holy Places of Egypt, Sinai, Palestine and Syria in 1384, [by Frescobaldi, Gucci and Sicoli] Jerusalem 1948.

Hoade, Eugene Western pilgrims ... The itineraries of Fr. Simon Fitzsimons-

Bellorini, Fr. Theophilus & Hoade, Fr. Eugene, A Voyage beyond the Seas ... Translated by Fr. T. Bellorini ... and Fr. E. Hoade [from the edition of B. Bagatti], etc. Jerusalem, Franciscan Press 1945

March

The Carpetbagger

It all started with Plutarch. In his life of Julius Caesar, he tells the story of the first meeting of Julius Caesar and Cleopatra:

“So Cleopatra, taking only Apollodorus the Sicilian from among her friends, embarked in a little skiff and landed at the palace when it was already getting dark; and as it was impossible to escape notice otherwise, she stretched herself at full length inside a bed-

Plutarch – The Life of Julius Caesar Loeb Classical Library Edition 1919

The story became a key part of the mythology that grew up around Cleopatra, and helped to elevate her into one of those historical personalities who have become symbolic as well as significant. Along the way, due to an alternative translation and the fact that at one time ‘carpet’ referred to a type of coarse fabric, the bag for holding bedding became a floor carpet.

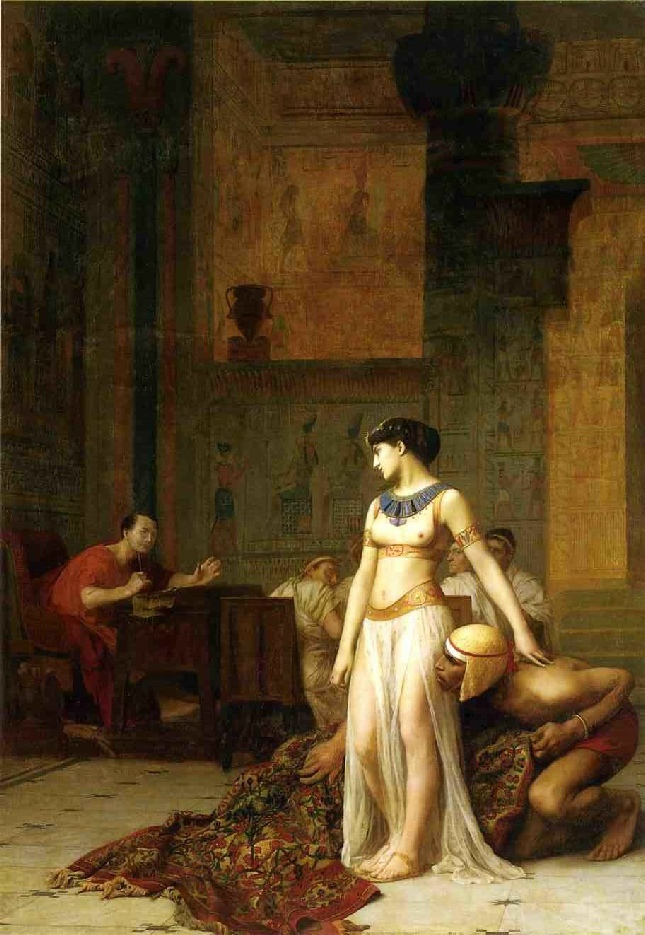

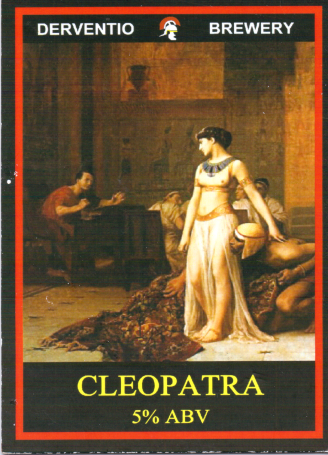

In December 1860 the novelist Prosper Mérimée (whose story was the basis of the opera Carmen) suggested the incident as the subject for a painting to the artist Jean-

Sadly, La Païva herself was not enamoured with the painting, and returned it, but Gérôme went on to exhibit it at the Paris Salon of 1866, and later at the Royal Academy in London in 1871. Although it was sold in the 1870s to the American banker Darius Mills, and remained in his family until 1990, this early exposure helped to popularise the picture, and it was widely reproduced as photographs and engravings by the artist’s father-

The Serpent of the Nile

In itself, the genesis and history of the painting says a lot about the way in which Ancient Egypt (strictly speaking, of course, Ptolemaic Egypt) was understood in Western Europe and North America, but what is just as interesting is the way in which, having achieved iconic status, it could then go on to inspire secondary works.

In 1882, the British and French governments intervened in Egyptian domestic politics in an attempt to reinforce the authority of the Khedive Tewfiq, who had been unable to resist demands for reform by nationalist elements led by an Egyptian army colonel, Ahmed Arabi, which led to the formation of a government with Arabi as Minister of War. In June of 1882, Alexandria, which had a large European population, erupted in rioting. Following the expiry of a British ultimatum that gun batteries defending the city should be dismantled, without this happening, British ships bombarded the city, the gun batteries were destroyed, and the city was eventually occupied by British naval troops. After an attempted advance by British forces from Alexandria to Cairo was unsuccessful, more troops were landed in the Suez Canal zone, and Egyptian forces under Arabi were defeated at the Battle of Tel el Kebir. Although Egypt was never formally a British colony, this was the start of a British occupation that was to last until the 1950s.

In 1882, the British and French governments intervened in Egyptian domestic politics in an attempt to reinforce the authority of the Khedive Tewfiq, who had been unable to resist demands for reform by nationalist elements led by an Egyptian army colonel, Ahmed Arabi, which led to the formation of a government with Arabi as Minister of War. In June of 1882, Alexandria, which had a large European population, erupted in rioting. Following the expiry of a British ultimatum that gun batteries defending the city should be dismantled, without this happening, British ships bombarded the city, the gun batteries were destroyed, and the city was eventually occupied by British naval troops. After an attempted advance by British forces from Alexandria to Cairo was unsuccessful, more troops were landed in the Suez Canal zone, and Egyptian forces under Arabi were defeated at the Battle of Tel el Kebir. Although Egypt was never formally a British colony, this was the start of a British occupation that was to last until the 1950s.

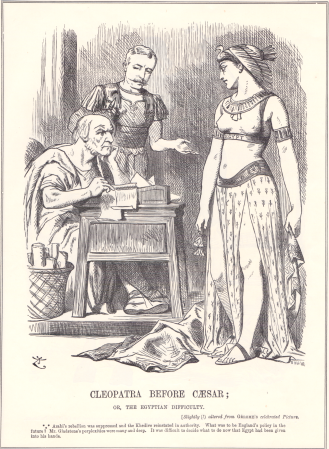

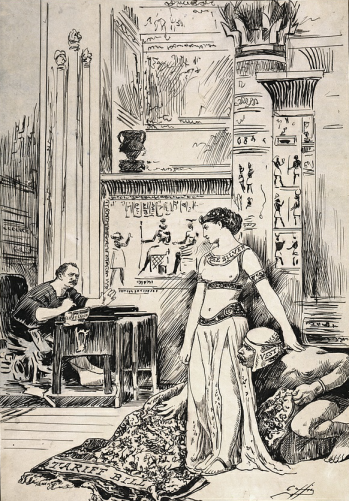

Against the background of these events, Punch published a cartoon based on Gérôme’s picture, titled ‘Cleopatra Before Caesar; or, the Egyptian Difficulty’. A note described it as “[Slightly (!) altered from GÉROME’S celebrated Picture.” It was later republished in 1897 with a gloss to remind readers of its context now that the events were no longer topical. In it, Gladstone takes the place of Julius Caesar, with the figure of Cleopatra in front of him identified as the personification of Egypt by a label on her bodice. To Gladstone’s left is a figure in Roman military uniform, representing Sir Garnet Wolseley, who commanded British forces at Tel el Kebir. In the 1897 version, the gloss read:

“Arab’s rebellion was suppressed and the Khedive reinstated in authority. What was to be England’s policy in the future? Mr Gladstone’s perplexities were many and deep. It was difficult to decide what to do now that Egypt had been given into his hands.”

Understandably, the grouping of the main figures is now closer to fit the cartoon format, and Caesar’s servants and Apollodorus have disappeared. More significantly, the figure of Cleopatra, bareheaded in the original, now wears a vulture crown emphasising her personification of Egypt. She also now clutches in her right hand two rather wilted looking lilies in an Ancient Egyptian style. Where the original Caesar raises one hand in what may be a gesture of surprise, Gladstone rests his chin on his hand in a thoughtful pose. The figure of Wolseley, gesturing towards Cleopatra/Egypt, is completely new.

Silver Lady

Before considering how this image compares to Gérôme’s in its depiction of Ancient Egypt, it is worth considering another use of the same painting in a quite different context in 1896. This appeared in The Washington Post, and was identified as being “From the famous painting by J L Gerome.” This time, the Caesar figure is that of Grover Cleveland, identified by a label on the desk in front of him. Cleopatra is without vulture crown and lilies, but the Apollodorus figure is back, as a caricature of one of Cleveland’s political opponents. This time, Cleopatra is labelled on her necklace as ‘Free Silver’, and another label on the carpet refers to a ‘Tariff Bill’.

Here, the political references were not to Egypt itself. Grover Cleveland, 22nd and 24th President of the United States of America, was a Democrat, and an economic liberal and fiscal conservative. He was an opponent of high trade tariffs and so-

Here, the political references were not to Egypt itself. Grover Cleveland, 22nd and 24th President of the United States of America, was a Democrat, and an economic liberal and fiscal conservative. He was an opponent of high trade tariffs and so-

Despite their very different political contexts, and one remaining closer in composition to the original painting, both cartoons use it in a similar way. Caesar, and by extension Gladstone and Cleveland, is shown as mature and statesmanlike, interrupted from the administration of an empire or a great nation by a scantily clad and bare-

‘A thousand of bread, a thousand of beer…’

It is doubtful now whether a cartoonist could rely on their audience being familiar enough with Gérôme’s picture to use it as the basis for a cartoon, but it, and its evocation of the charms of Egypt are still being employed. In 2005 a micro-

Until next time,

Ankh Wedja Seneb

Chris

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cleopatra_and_Caesar_%28painting%29

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_Pa%C3%AFva

(See references in articles.)

| The Elderly Lady's Elephant |

| Murder, Mystery, Monuments and Mummies |

| Necropolis of the North West |

| Picture This |

| Newsletter subscription form |

| Egypt in England Newsletter 2016 |

| Egypt in England Newsletter - 2015 |

| Egypt in England Newsletter 2014 |

| Egypt in England Newsletter - 2013 |